source link:

1、http://blog.bignerdranch.com/1907-hooked-on-dtrace-part-1/

2、http://blog.bignerdranch.com/1968-hooked-on-dtrace-part-2/

3、http://blog.bignerdranch.com/2031-hooked-on-dtrace-part-3/

4、http://blog.bignerdranch.com/2150-hooked-on-dtrace-part-4/

===========================================================

Part 1

My day-to-day work is building Mac and iOS software. That means I spend a fair amount of time inside of the Usual Tools for that. Xcode. Interface Builder. Instruments. gdb and lldb. There’s another tool out there that many programmers don’t think to reach for, and that’s DTrace. Just the other day I needed to see how an app I inherited was working with NSUndoManager so I could fix some weird behavior. With DTrace, I quickly found out where every NSUndoManagerwas created (turned out to be four), and more importantly, where each one was being used, complete with stack traces.

You can do that with debuggers. You can set breakpoints with regular expressions. And perhaps add some scripts, or Xcode breakpoint settings for particular calls. You could also write some lldb python script to do some magic. Sounds like a lot of work. My DTrace thing? One command:

# dtrace -n 'objc57447:NSUndoManager*::entry { printf("%x", arg0); ustack(20,0); }' -n 'objc57447:NSUndoManager:-init:return { printf("%x", arg1); ustack(20, 0); }'

OK, so that looks like gibberish, like many command lines someone pulls out of their shell history and posts saying “Look at me! Look how wonderful I am!” That being said, DTrace is a superbly powerful tool, and is useful for more than system administrators and kernel developers. Before I can really dig into this command, and the usefulness of DTrace for Objective-C developers, I’ll cover a little bit of DTrace first. Later on I’ll cover my undo manager story. Also my colleague at the Ranch Adam Preble hinted about using DTrace in Objective-C in an earlier posting. We’ll dig into exactly what he did to track down that problem with DTrace.

SO, WHAT IS IT?

What is this “DTrace” thing? It stands for “Dynamic Tracing”, a way you can attach “probes” to a running system and peek inside as to what it is doing. It was created by Sun for Solaris, and was ported to the Mac in the Mac OS X 10.5 “Leopard” time frame. DTrace is not available on iOS, but you can use it in the simulator.

Imagine being able to say “whenever malloc is called in Safari, record the amount of memory that’s been asked for.” Or, “whenever anyone opens Hasselhoff.mov on the system, tell me the app that’s doing so.” Or, “show me every message being sent to this particular object.” Or, “show me where every NSUndoManager has been created, and tell me the address of that object in memory.”

DTrace lets you do this by specifying probes. A probe describes a function, or a set of functions, to intercept. You can say “when some function is about to run, do some sequence of steps”, or “when some function exits, tell me what the return value is, and where in that function it actually returned.” What’s neat about DTrace is that this happens dynamically (hence the name). You don’t have to do anything special to participate. Any function or method in your code can be traced.

You command DTrace by writing code in the “D Language”, which is not related to that other D Language. DTrace’s D is a scripting language that has a strong C flavor, so much of C is available to you. It gets compiled by the dtrace command into bytecode, shipped to the kernel, where it runs. It’s run in a safe mode to minimize impact on the system, so there’s no looping , branch statements, or floating point operations.

A D script is composed of a sequence of clauses which look like this:

syscall::read:entry /execname != "Terminal"/ { printf ("%s called read, asking for %d bytes ", execname, arg2); }

THE PROBE DESCRIPTION

There’s four parts to a DTrace clause. The first line is a probe description:

syscall::read:entry

It’s a four-tuple (don’t programming nerds love terms like that?), that specifies four things:

- A provider. This is the entity that provides access to classes of functions. A common provider is syscall, which lets you trace Unix system calls like read and write system-wide. There’s another provider called pid that lets you trace functions inside of a particular program. You’ll see that in part 2. The objc provider lets you poke around in Objective-C land, and you’ll see that in part 3. There’s a lot of other providers available, too.

- A module. This depends on the provider. Some providers don’t have modules. Some providers let you specify a particular shared library in the module. Perhaps you only wanted to trace some functions inside of libxm2.dylib – you could put that in the module.

- A function. This is the name of the function you want to pay attention to.

- A name. The name also depends on the provider, but most let you specify

entry, to run some D code before the function starts running orreturnto run some D code after the function has exited.

The parts of the probe description are separated by colons. You have to have all the colons, even if a spot is empty. Leaving an entry acts like a wildcard. Speaking of wildcards, you can use * and ? in the style of shell globbing : * matches zero or more characters, and ? matches exactly one.

So what does the probe description mean?

syscall::read:entry

It means: for the syscall provider, any module, we’re interested in the read function. Specifically, right before it starts running. Now, whenever that happens (someone calls read), the rest of the clause will be evaluated.

THE PREDICATE

Next up is the predicate, delimited by two slashes. It’s optional. The expression is evaluated, and if it evaluates to a true (non-zero) value, the D code gets run. The predicate above is:

/execname != "Terminal"/This means, if the current executable name (execname is a built-in variable) is Terminal, don’t do anything. The dtrace command will be printing stuff out in the Terminal, so you know it’s going to be reading stuff. No need to see it clutter up the output for this particular example.

LAST ACTIONS HERO

The last part, the code in braces, are known as the actions. The actions are run when the probe description matches a firing function, and the predicate evaluates to true. In this case, the actions just print out some stuff:

{ printf ("%s called read, asking for %d bytes ", execname, arg2); }

In particular, it prints out the name of the executable, and the number of bytes read.

What’s that arg2? It’s a built-in variable for the third argument to read. (You can guess there’s also an arg0, arg1, and so on). Recall read()’s prototype:

ssize_t read (int fileDescriptor, void *buffer, size_t bytesToRead);

Number of bytes to read is the third argument, so it’s the second index. You could, if you wanted to, have your actions block examine which file descriptor is being used, where the destination buffer is, and how much they want to read.

RUN, RUN AWAY

Now to actually run this stuff. The dtrace command needs to be run as root – with superuser privileges. Ordinarily you’d use sudo to run a command as root, but some DTrace behaviors don’t work reliably when run with sudo, so you can start a root shell with sudo -i, or give it a shell, like with sudo bash.

Assuming that script above is saved in a file named read.d, you would run it like

# dtrace -s read.d dtrace: script 'read.d' matched 1 probe CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 2 115 read:entry WebProcess called read, asking for 32768 bytes 2 115 read:entry WebProcess called read, asking for 32768 bytes 1 115 read:entry mds called read, asking for 147424 bytes 0 115 read:entry fseventsd called read, asking for 189799 bytes 0 115 read:entry Activity Monito called read, asking for 27441 bytes 0 115 read:entry Activity Monito called read, asking for 19253 bytes 0 115 read:entry Activity Monito called read, asking for 11061 bytes 1 115 read:entry Propane called read, asking for 32768 bytes 2 115 read:entry Google Chrome H called read, asking for 1 bytes ^C

When run, dtrace tells you the number of probes it matched, and then prints out a new line when the probe fires. It tells you what CPU it triggered on, the ID of the probe, the description of the probe that fired, and the text generated by the printf statement.

A lot of stuff is happening on the system, even though it kind of looks like it’s just sitting there. When you’re done watching the reads scroll by, type Control-C to terminate dtrace

EXPLORING THE COMMAND

dtrace has a man page the describes the command-line flags, and there are numerous books and online tutorials you can explore. There’s also a nice set of slides from a DTrace Bootcamp.It’s not a Mac-only technology, but a great deal is common between Solaris and the Mac. Here are some commands:

-l (dash ell) tells dtrace to list all probes. If there are no other arguments, dtrace lists all the probes it knows about out of the box, without paying attention to any particular running program:

# dtrace -lYou’ll get a lot of output if you actually try it. On my systems there are over 200,000 individual probes. You can redirect and pipe through grep, or you can redirect it to a file and poke around with your favorite text editor.

You can limit the output to just the probes that match a particular description. -n lets you specify a probe by “name”, by providing a probe description:

# dtrace -l -n 'syscall::read:entry'This tells you it found read:

ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 115 syscall read entry

You can also use wildcards:

# dtrace -l -n 'syscall::read*:entry' ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 115 syscall read entry 225 syscall readlink entry 349 syscall readv entry 901 syscall read_nocancel entry 931 syscall readv_nocancel entry

Lots of different kinds of read functions.

KING OF THE ONE-LINERS

DTrace is great for one-liners – single commands that do stuff. read.d from above can be condensed to a single line:

# dtrace -n 'syscall::read:entry /execname != "Terminal"/ { printf ("%s called read, asking for %d bytes

", execname, arg2); }'Why is this useful, outside of “Hey look at me”? You can experiment entirely on the command line, without having to bounce between and editor an a shell. I find my DTrace stuff tends to be very ad-hoc. “What is this thing doing, right now” and “how do I find out this one piece of information I need, right now.” I tend not to write too many scripts that live in files. It’s a developerism, using little throw-aways to diagnose an immediate problem. Folks who administer machines for a living often have libraries of scripts that monitor and diagnose their systems.

A PRACTICAL USE

So What. Big Deal. You can see who is reading stuff. Is there any actual use you can put this stuff to, right now, before getting to the pid and objc providers later? Why yes!

A friend of mine got an app rejected from the Mac AppStore because his app was (supposedly) attempting to open the Info.plist in DiskArbitration.framework in read/write mode. An app really shouldn’t be trying to write to anything in a system framework. Sad thing is, his app wasn’t doing this, at least not explicitly. It just used the framework, including it in Xcode in the usual manner and then calling its API. The framework was being loaded by the usual app startup machinery. It was an unjust accusation, but there’s really no recourse, short of resubmitting the app and hoping it works.

Wouldn’t be nice if you could catch every open being done by a program, and see what access flags it’s passing? You could take this output and see “oh yeah, for some reason I’m opening this read/write” and do some debugging, or else have some evidence for “I don’t see any wrongdoing”. Sounds like a great application of DTrace.

Together we cooked up a script like this:

syscall::open:entry /execname == "TextEdit"/ { printf("Opening %s with flags %x ", copyinstr(arg0), arg1); }

(OBTW, that copyinstr action in there copies a string from the running program into dtrace-land so it can be printed.)

We started this script running in dtrace, and then launched the app. As expected, all of the framework Info.plist opens were with zero flags, which means read-only:

... 0 119 open:entry Opening /System/Library/Keyboard Layouts/AppleKeyboardLayouts.bundle/Contents/Info.plist with flags 0 0 119 open:entry Opening /System/Library/Keyboard Layouts/AppleKeyboardLayouts.bundle/Contents/Info.plist with flags 0 2 119 open:entry Opening /System/Library/Frameworks/AppKit.framework/Resources/Info.plist with flags 0 ...

With this output, plus the script, he was able to make a case that no wrongdoing happened. The app was subsequently approved.

SOME FUN THINGS TO TRY

Here are some commands to play around with.

See what files are being opened by Time Machine during a backup, including the files being backed up:

# dtrace -n 'syscall::open*:entry /execname == "backupd"/ { printf ("%s", copyinstr(arg0)); }'Replace “backupd” with “mdworker” to see what Spotlight is indexing on your system.

See every system call being made, what it is, and who’s calling it. This uses another built-in variable, probefunc, to tell you which function actually triggered. You don’t really know otherwise because wildcarding is in use. There’s also probeprov, probemod, and probename, so you can examine the entire probe description inside of the clause body.

# dtrace -n 'syscall:::entry { printf ("%s called %s", execname, probefunc); }'See all the processes launching on your system. Especially fun when doing work in the terminal:

# dtrace -n 'proc:::exec-success { trace(execname); }'Feel free to play around. You can’t damage your system with dtrace, unless you take special pains to do so.

===========================================================

Part 2

The other day I was chatting with one of my colleagues at the Ranch and he asked me where I get my blog ideas. One fertile idea-ground is what sometimes happens during day-to-day work, solving a potentially hard problem in a way that’s actually pretty easy. And then I discover there’s a fair amount of ground work needed to understand it. Hence these multi-part War and Peace epics.

The objc provider in DTrace is the ultimate goal. But to understand the objc provider, you need to grok the basics of DTrace. You also need to know how DTrace traces functions inside of a particular process. The pid provider does this, and happily the objc provider works in a similar manner.

THE PID PROVIDER

The pid provider lets you trace functions inside of a particular process. The name comes from Unix parlance, where pid means “process ID”. getpid() is the system call to get your process ID.

The syscall provider you saw last time lets you monitor system calls across the entire machine, and you can use predicates to limit the view to just one process. The syscallprovider doesn’t let you trace things that live in libraries, like malloc(). The pid provider exposes all of the available functions and data types for single. particular process. Want to see how Safari uses malloc? You can ask the pid provider.

A probe description for the pid provider follows the same provider:module:function:namepattern :

pid3321:libsystem_c.dylib:malloc:entry

This says, for process id 3321, in libsystem_c.dylib, the malloc function, whenever it enters, go do stuff. For fun, see what Safari is doing. Figure out Safari’s process ID. An easy way to do that is to peek in Activity Monitor:

You can also ps and grep to get it from the command-line:

$ ps auxw | grep Safari

And then construct a command putting the process ID after “pid”

# dtrace -n 'pid8880::malloc:entry { printf ("Safari asking for %d bytes", arg0); }' dtrace: description 'pid8880::malloc:entry ' matched 2 probes CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 2 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 24 bytes 2 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 24 bytes 1 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 98304 bytes 2 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 4 bytes 0 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 8 bytes 1 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 98304 bytes 2 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 4 bytes 2 3756 malloc:entry Safari asking for 8 bytes

Sure enough, we’ve got code running for each call to malloc. Everything else you know about DTrace applies now. The pid provider is just another provider that you can hang other code off of.

THAT ANNOYING PROCESS ID

Before getting into some more interesting stuff about the pid provider, there’s an elephant in the room. That process ID. The pid provider needs to know what process to introspect, and you do that by providing the numerical process ID.

That’s a pain in the neck. There’s three things that you can do.

The first thing you can do is to just paste the process ID in your command. It’s up to you to figure out the process ID of interest. That’s fine for one-off commands, and is how I sometimes roll.

The second option is to use a variable, like $1, for the process ID, and then pass the process ID on the command line:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$1::malloc:entry' 8880 ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 3756 pid8880 libsystem_c.dylib malloc entry 6204 pid8880 dyld malloc entry

That way you don’t need to retype the whole command or edit a chunk in the middle. This is especially useful for scripts that live in files. Refer to the process ID via $1 and you can use that script against any process.

These dollar-variables are generic. You can pass multiple extra parameters to dtrace and they’ll be available as $1, $2, etc. You might have a threshold you want to change from run to run, like only report functions that try to malloc more than 4 megs at a time.

-C TO SHINING -C

The third option is to let DTrace run the program for you, with the -c option. You give dtrace -c and a path to a program. dtrace will run the program and start its tracing. When the program exits, the tracing finishes. That’s how I usually run DTrace experiments these days – trace some stuff in an application, and then exit while I go analyze the results.

The big advantage to running with -c is easy access to the process ID : just use the $targetvariable.

Here’s a simple C program:

#include <stdio.h> // clang -g -Weverything -o simple simple.c int main (void) { printf ("I seem to be a verb "); return 0; } // main

All it does is print out a line. I wonder if this calls malloc as part of its work. Let’s see:

# dtrace -n 'pid$target::malloc:entry' -c ./simple dtrace: description 'pid$target::malloc:entry' matched 2 probes I seem to be a verb dtrace: pid 11213 has exited CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 10 7518 malloc:entry

Sure enough, it was called once. I wonder where. There’s a built-in action called ustack which gives you the stack trace in user-land:

# dtrace -n 'pid$target::malloc:entry { ustack(); }' -c ./simple dtrace: description 'pid$target::malloc:entry ' matched 2 probes I seem to be a verb dtrace: pid 11224 has exited CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 12 9817 malloc:entry libsystem_c.dylib`malloc libsystem_c.dylib`__smakebuf+0x7f libsystem_c.dylib`__swsetup+0x99 libsystem_c.dylib`__vfprintf+0x61 libsystem_c.dylib`vfprintf_l+0x2d7 libsystem_c.dylib`printf+0xc8 simple`main+0x1d libdyld.dylib`start simple`0x1

So, printf called vprintf called __vfprintf, into something called __swsetup, which makes a buffer, which then calls malloc. Pretty neat. You can pass an argument to ustack to only print out the top N functions of the stack trace if you don’t care about its ancestry all the way back to before main.

One of the nice things about -c is that your script ends when the program exits. Otherwise dtrace will run forever, until the script itself decides to bail out with the exit() action, dtrace gets interrupted by Control-C, or something catastrophic happens like the user logging out, the system rebooting, or the heat death of the universe arrives.

SEEING PROBES

What are some of the probes you look at with the pid provider? You can take a look! Thesimple program from above is pretty basic, so take a look at that. Recall that -l (dash-ell) will list probes, and -n lets you provide a probe description. If you use -c (run a program) and -l,dtrace will forgo actually running the program, and just emit the list of probes. Try this:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c ./simple > simple-probes.txtBe sure you have entry at the end. You’ll see why in a bit. Poke around simple-probes.txtin your favorite editor. You’ll see calls provided by libcache.dylib, libSystem.B.dylib, common crypto, grand central dispatch, and all sorts of other goodies. In fact, on my system, I have over fourteen thousand of them:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c ./simple | wc -l 14256

You’re not limited to your own programs. You can look at system utilities:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c /bin/ls > ls-probes.txtYou can also look at Cocoa programs. Just dig into the bundle to find the executable

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEdit > textedit-probes.txtHere’s a smattering:

204547 pid11399 CoreFoundation CFMachPortGetPort entry 204548 pid11399 CoreFoundation CFDictionaryGetValue entry 204549 pid11399 CoreFoundation CFBasicHashFindBucket entry 204550 pid11399 CoreFoundation __CFDictionaryStandardHashKey entry 204551 pid11399 CoreFoundation CFBasicHashGetSpecialBits entry 204552 pid11399 CoreFoundation __CFRunLoopDoSource1 entry 204553 pid11399 CoreFoundation CFRetain entry ... 311688 pid11399 libxml2.2.dylib _xmlSchemaParseTimeZone entry 311689 pid11399 libxml2.2.dylib _xmlSchemaParseGMonth entry 311690 pid11399 libxml2.2.dylib _xmlSchemaParseTime entry 311691 pid11399 libxml2.2.dylib xmlStrndup entry ... 312236 pid11399 libz.1.dylib compress2 entry 312237 pid11399 libz.1.dylib compress entry 312238 pid11399 libz.1.dylib compressBound entry 312239 pid11399 libz.1.dylib get_crc_table entry ... 364759 pid11399 CoreGraphics _CGSReleaseColorProfile entry 364760 pid11399 CoreGraphics _CGSUnlockWindowBackingStore entry 364761 pid11399 CoreGraphics CGSGetWindowLevel entry 364762 pid11399 CoreGraphics CGWindowContextCreate entry 364763 pid11399 CoreGraphics CGContextCreate entry 364764 pid11399 CoreGraphics CGContextCreateWithDelegate entry 364765 pid11399 CoreGraphics CGRenderingStateCreate entry ...

Want to trace stuff in CoreFoundation or CoreGraphics? Go right ahead. Want to see if your program is compressing anything with libz? Be my guest.

If you look closely at this set of probes (search for “AppKit” or “Foundation”) you’ll see some Objective-C stuff, so you can run some experiments with just the pid provider. But it’s kind of awkward.

NAME AND NAME, WHAT IS NAME?

Recall that the last chunklet of the probe description is called the name. That’s a pretty vague term. The pid provider has three kinds of names. entry, return, and a number.

When you specify entry, your DTrace clause will start processing right before the specified function starts running. You can look at arguments passed to the the function with the built in variables arg0, arg1, and so on.

When you specify return, your DTrace clause will start processing right after the function returns. arg1 contains the return value from the function. arg0 contains the instruction offset from the beginning of the function where the return happened. That’s pretty cool – inside of your DTrace script, you could (depending on your understanding of the function in question) determine when the function bailed out early, or finished to completion. Or you could tell when a function returned normally, and when it returned in an error path. You can answer questions like “what is the percentage of early bailouts for this function?”

So that number you could provide as a name for a pid provider probe? It’s an offset into the function. That means you can have your DTrace stuff trigger at an arbitrary point inside of the function.

This means that each instruction is a potential dtrace probe. Earlier where I said to be sure to use entry in the probe description? What happens if you forget it? The dtrace command will take a long time to run. And then you’ll have a whole lot more probes. Here’s simple, looking at entry probes:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c /bin/ls | wc -l 14851

And here it is without:

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::' -c ./simple | wc -l 667217

Atsa lotsa probes.

THE PID TAKEWAY

So what’s the takeaway from the pid provider?

- You can trace functions inside of a single process

- You can explore the exported symbols of a program (this can be interesting / educational in its own right)

entrylets you look at function arguments;returnlets you look at the return value (arg1) and return instruction (arg0)- You can trace at a granularity of individual instructions

- You need to provide the process ID, either explicitly in the probe description, via an argument to dtrace and accessed with

$1, or use$targetand run dtrace with-cand supplying the path to an executable

TIME OUT FOR VARIABLES

DTrace becomes a lot more interesting when you can play with variables. Variables in DTrace can be used undeclared. You can also declare them, and their type is set on their first assignment. You can’t declare and assign at the same time. You can have variables of just about any C type, like ints, pointers, arrays and even structures. If you have a pointer to a structure, you can dig into it. The main limitation is no floating point variables.

DTrace has three scopes for variables. Variables are global by default.

Here is a way of figuring out how long a function took to run, using the built-in timestampvariable, which is a wall-clock timestamp, in nanoseconds. (There’s also vtimestamp, which is an on-cpu-time timestamp, also in nanoseconds):

/* run with * dtrace -s malloctime.d -c ./simple */ pid$target::malloc:entry { entry_time = timestamp; } pid$target::malloc:return { delta_time = timestamp - entry_time; printf ("the call to malloc took %d ns", delta_time); }

When malloc is entered, the timestamp is stored in the global variable entry_time. Whenmalloc exits, the stashed value is subtracted from the current timestamp, and printed. You’d run it like this:

# dtrace -s malloctime.d -c ./simple dtrace: script 'malloctime.d' matched 4 probes I seem to be a verb dtrace: pid 12006 has exited CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 6 57313 malloc:return the call to malloc took 15066 ns

We live in a multithreaded world, so using a global for storing the start timestamp is not a great idea. DTrace has two additional variable scopes: clause-local and thread-local.

“Clause-local variables” are just a fancy name for local variables. They’re decorated with this-> in front of the variable name, come into being inside of the actions block, and are discarded when the actions block ends. delta_time above would become this->delta_time:

This makes the delta variable safer because there is no chance another threads could change its value:

pid$target::malloc:entry { entry_time = timestamp; } pid$target::malloc:return { this->delta_time = timestamp - entry_time; printf ("the call to malloc took %d ns", this->delta_time); }

There’s still a problem with this, though, in a full-on multithreaded program. Thread A might enter malloc, and record the timestamp. Thread B then enters malloc and records its timestamp, clobbering the previous value. When Thread A finally returns, the reported time will be too short. Bad data could lead to bad decisions.

In DTrace, “Thread-local Variables” are prefixed with self->, and are (as the name implies) kept on a per-thread basis. To fix the bad malloc-time problem, you’d store the timestamp in a thread local variable on entry, pull it out on return, and do your math. Because thread local variables need to stick around, you should “collect” them when you are finished with them by assigning them to zero. Here’s the updated version:

pid$target::malloc:entry { self->entry_time = timestamp; } pid$target::malloc:return { this->delta_time = timestamp - self->entry_time; printf ("the call to malloc took %d ns", this->delta_time); self->entry_time = 0; }

D is indeed a real programming language, because there’s always something that needs fixing in the code you write. There’s still one problem with this. What happens if you start tracing the program while malloc is already in flight? The return probe will fire, the timestamp calculation reaches for self->entry_time, and there’s nothing there. Its value will be zero, leading todelta_time becoming timestamp - 0, which will be a humongous value. You’ll need something to prevent the return probe from running when there’s no entry_time.

Predicates to the rescue! Add a predicate to skip the return probe’s action body if theentry_time thread-local variable has not been set:

pid$target::malloc:entry { self->entry_time = timestamp; } pid$target::malloc:return /self->entry_time/ { this->delta_time = timestamp - self->entry_time; printf ("the call to malloc took %d ns", this->delta_time); self->entry_time = 0; }

Of course, this isn’t a problem with simple, but can bite you when you’re doing Real Investigations.

SOME FUN THINGS TO TRY

You can see all of the functions called by a program:

# dtrace -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c /bin/echoYou can see there’s a lot of work involved in just getting a program up and running.

See the different modules available in a program (thanks to rancher Bill Phillips for the processing pipeline)

# dtrace -l -n 'pid$target:::entry' -c ./simple | awk '{print $3}' | sort | uniqDtrace has “associative arrays”, which act like dictionaries or hashes in other languages. They look like regular variables, indexed with square brackets. You can use any value (and any combination of values) as a key. You can make a cheap time profiler by storing the start times for functions in an associative array:

/* run with * dtrace -q -s malloctime.d -c ./simple */ pid$target:::entry { entry_times[probefunc] = timestamp; } pid$target:::return /entry_times[probefunc]/ { this->delta_time = timestamp - entry_times[probefunc]; printf ("the call to %s took %d ns ", probefunc, this->delta_time); entry_times[probefunc] = 0; }

Add the -q flag when running it to suppress dtrace‘s automatic display, which makes the output hard to read. But here’s a sample from the middle of the run:

# dtrace -q -s ./call-timings.d -c ./simple ... the call to __swsetup took 255014 ns the call to __get_current_monetary_locale took 14135 ns the call to __get_current_numeric_locale took 13170 ns the call to localeconv_l took 67980 ns the call to memchr took 5461 ns the call to memmove$VARIANT$sse42 took 11023 ns the call to __fflush took 5440 ns the call to __swrite took 5571 ns the call to __write_nocancel took 19920 ns the call to _swrite took 47466 ns the call to __sflush took 59219 ns the call to __sfvwrite took 119338 ns the call to vfprintf_l took 483334 ns the call to printf took 517681 ns ...

Run this and send the output to a file, and browse around. You should find where main ends, and then all the process tear-down happens. Run it against your own programs.

===========================================================

Part 3

As you’ve seen before, DTrace can give you a huge amount of visibility into the guts of your computer. You saw the syscall provider which lets you attach probes to system calls, those functions that let you take advantage of services from the kernel. You also saw the pid providerwhich lets you look inside individual processes and trace the function activity inside of there.

This time around is the objc provider, the one that started this whole ride. It lets you trace Objective-C methods inside of an individual process. A typical probe description for the objc provider looks like this:

objc2342:NSImage:-dealloc:entry

Which says, for process id 2342, for objects of the NSImage class, whenever -dealloc is entered, evaluate some D code.

The parts of the probe description of the objc provider are:

probeprov: The provider – objc + the process IDprobemod: A class name, such asNSWindow, or class name and a category, likeNSWindow(NSConstraintBasedLayout)probefunc: A method name / selectorprobename:entry,return, or an instruction offset, like thepidprovider

The same process ID annoyances happen here like they do with the pid provider. You can provide an explicit process ID in the probe description, pass an argument and refer to it with $1, or you can use $target coupled with the -c option to tell dtrace to run or examine a program. Don’t forget you can dig into Cocoa application bundles to get to the crunchy executable inside. Also don’t forget that any parts of the probe description that are omitted act as wildcards, along with the globbing characters * (match zero or more) and ? (match one).

You saw how to use the pid provider to list all the function probe points available in a program. You can use the objc provider to do the the same thing, but with methods:

# dtrace -l -n 'objc$target:::entry' -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEdit > textedit-probes.txt

Feel free to poke around this file with your favorite editor. Search around for your favorite classes.

Like with Objective-C, class methods are prefixed with +, and instance methods prefixed with -. For example, a class method:

# dtrace -l -n 'objc$target:NSView:+initialize:entry' -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEdit ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 24101 objc7385 NSView +initialize entry

as well as an instance method:

# dtrace -l -n 'objc$target:NSFontManager:-init:entry' -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEdit ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 24101 objc7391 NSFontManager -init entry

QUESTIONS ABOUT COLONS

There’s one hitch. How do you specify a method name that contains colons? What if you wanted to do stuff whenever someone called NSDicitonary -getObjects:andKeys:? What happens if you try this this command:

# dtrace -l -n 'objc$target:NSDictionary:-getObjects:andKeys::entry ...

The command will smack you down with an error:

dtrace: invalid probe specifier. neener neener.

DTrace uses colons. Objective-C uses colons. If you need to use them both, who wins? It’s DTrace’s playground, so it wins. You need to finesse your probe descriptions using wildcarding, by replacing the colons in the selector with question marks:

# dtrace -l -n 'objc$target:NSDictionary:-getObjects?andKeys?:entry' -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEdit ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 185597 objc7462 NSDictionary -getObjects:andKeys: entry

YAY! FINALLY!

Two postings and some change later, I can finally tell you about some practical applications (that is, fun stuff) you can do with DTrace in Objective-C land.

I had a problem a couple of weeks ago. My team inherited a large code base and we’re needing to fix bugs, improve performance, and turn around a new release on a short schedule. One of the bugs I discovered (and subsequently needed to fix) related to undo. You could type text in one text field and do all sorts of editing. If you then navigate to another text field, the Undo menu item was still enabled. Choosing Undo at this time would apply the changes from the first text field (insert characters at this location, remove characters in this range) to the second text one, corrupting the text in the process. Subsequent Undos wouldn’t work because everything’s messed up inside. The twist is that this is a Mac executable, but an iOS codebase, using the Chameleon compatibility library.

One option was to just turn off Undo support entirely. That would have been kind of mean, because it’s easy to accidentally do something stupid when editing text and immediately reach for command-Z to undo it. It’s a nice feature. The next thought was to grab the appropriateNSUndoManager and call -removeAllActions when the text field loses first responder status. That way the user could Undo while editing, and then we commit it when navigating away. It’s a good compromise between “no undo” and cooking up full-featured undo for the whole app.

Unfortunately, because of the compatibility library, it wasn’t obvious where to get the right undo manager. There’s one you can get from UIDocument, and another from UIResponder, but neither one seemed to be useful. Time to pull out the big guns. Just where areNSUndoManagers coming from, and who is using them? If I can get this info while typing in one of the text fields, I can figure out the right undo manager to use.

Whenever faced with “who creates this” or “who calls this”, and I have no idea where to begin looking in the code, I reach for DTrace. First off is to see who is creating them. This was the first trial:

# dtrace -n 'objc$target:NSUndoManager:-init:return' -c /path/to/app 2 3721 -init:entry 3 3721 -init:entry 1 3721 -init:entry 3 3721 -init:entry

That’s semi-useful. I’m catching the return from -[NSUndoManager init]. This is telling me that four undo managers are being created. I could find out the address of these objects by printing out -init’s return value:

# dtrace -n 'objc$target:NSUndoManager:-init:return { printf("%x", arg1); }' -c /path/to/app 2 3721 -init:entry 102871da0 3 3721 -init:entry 10114b4f0 1 3721 -init:entry 101362270 3 3721 -init:entry 10113e2c0

Recall when using the return name of the pid or objc provider, arg0 has the instruction offset (which is not terribly useful for day-to-day work), and arg1 has the return value (useful!). -initreturns the address of the object it initialized, so I can see the actual addresses of the four undo managers running around the app. I could attach to the program with the debugger and inspect this memory, send messages to these objects, and unleash all kinds of ad-hoc mayhem.

WHO ARE YOU? WHAT DO YOU WANT?

Next, I wanted to ask was “just who are creating these undo managers?” I want to see stack traces. The ustack() action comes to the rescue. This command told me who created them:

#dtrace -n 'objc$target:NSUndoManager:-init:return { printf("%x", arg1); ustack(20); }' -c /path/to/app

This gives the top 20 functions on the call stacks. I’ll reduce the clutter here with what I found:

2 3721 -init:entry 102871da0 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager init] UIKit`-[UIWindow initWithFrame:]+0x9d AppOfAwesome`-[AppDelegate application:didFinishLaunchingWithOptions:]+0x275

A UIWindow is creating an undo manager

3 3721 -init:entry 10114b4f0 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager init] CoreData`-[NSManagedObjectContext(_NSInternalAdditions) _initWithParentObjectStore:]+0x297 CoreData`-[NSManagedObjectContext initWithConcurrencyType:]+0x8a AppOfAwesome`__35-[AppDelegate managedObjectContext]_block_invoke_0+0x7a libdispatch.dylib`dispatch_once_f+0x35 AppOfAwesome`-[AppDelegate managedObjectContext]+0xa8

Core Data is making one for the MOC

1 3721 -init:entry 101362270 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager init] UIKit`-[UIWindow initWithFrame:]+0x9d UIKit`-[UIInputController init]+0xd2 UIKit`+[UIInputController sharedInputController]+0x44 UIKit`-[UIResponder becomeFirstResponder]+0x13f UIKit`-[UITextView becomeFirstResponder]+0x5f UIKit`-[UITextLayer textViewBecomeFirstResponder:]+0x5f

Another window is being created due to the UITextView gaining focus.

3 3721 -init:entry 10113e2c0 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager init] AppKit`-[NSWindow _getUndoManager:]+0x1d5 AppKit`-[NSWindow undoManager]+0x17 AppKit`-[NSResponder undoManager]+0x22 AppKit`-[NSResponder undoManager]+0x22 AppKit`-[NSResponder undoManager]+0x22 AppKit`-[NSResponder undoManager]+0x22 AppKit`-[NSTextView undoManager]+0x8d AppKit`-[NSTextView(NSSharing) shouldChangeTextInRanges:replacementStrings:]+0x136

And then Cocoa is making one for the underlying NSTextView. Which one of this is my undo manager? Ask DTrace again, this time logging everything that’s being done by NSUndoManager:

# sudo dtrace -n 'objc57447:NSUndoManager*::entry { printf("%x", arg0); ustack(20); }'

This catches the entry into any NSUndoManager call. It prints out the first argument, which for the entry probename is the receiver of the message. It also prints out the stack. The * wildcard in the class name catches any categories, such as NSUndoManager(NSPrivate). How did I know there were categories? Do the “-l -n -c” trick to dump all the things out to a file and then search around in it.

Running this command emitted a bunch of output. Then I focused a text field and started typing, and saw even more stuff:

3 3777 -beginUndoGrouping:entry 10113e2c0 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager beginUndoGrouping] Foundation`-[NSUndoManager _registerUndoObject:]+0x7d AppKit`-[NSTextViewSharedData coalesceInTextView:affectedRange:replacementRange:]+0x1ea

This looks promising. The text view’s data is coalescing stuff (I love the word “coalesce”), which makes sense when typing. There’s also some undo grouping going on, which also makes sense when typing is happening:

3 3737 -_setGroupIdentifier::entry 10113e2c0 Foundation`-[NSUndoManager _setGroupIdentifier:] AppKit`-[NSTextViewSharedData coalesceInTextView:affectedRange:replacementRange:]+0x22e

These dudes are using the undo manager living at 0x10113e2c0, which is the one that came from inside of Cocoa. Neither of the Chameleon undo managers, nor the Core Data undo manager are involved. Luckily I could get ahold of the NSWindow underneath everything, get its-undoManager, and clear all of its actions at the proper time. That fixed the problem.

NO SCROLL I

Another bug we had was with a scrolling container of editable values that didn’t reset its scroll position when used to create a new object in the application. You could be editing an existing object with lots of stuff, scroll to the bottom, and then create a new object. The Panel of Stuff would still be scrolled to the previous bottom, clipping all the entry fields at the top. It was pretty confusing.

Grepping and searching around for UIScrollView didn’t show anything useful. There was a view controller object hierarchy using a third party library involved too. Maybe it was buried in there? No luck searching through its code. Before going along the route of setting random breakpoints in the app, I put a DTrace probe on UIScrollView‘s setContentOffset* along with a call to ustack() to see what changed it. Repro the bug, look at the output, and it turns out it was a UITableView (which itself is a UIScrollView subclass). Kind of a “duhhhh” momement, but luckily pretty quick to find. It was a piece of cake to reset the scroll position then.

LITERALLY SPEAKING

Back in November, Adam Preble wrote about some weird behavior he was seeing with the new Objective-C literals. To track down the problem he used DTrace to see all of the messages being sent to a particular object.

Just using a probe like

objc$target:::entry

would be pretty worthless – you get an incredible amount of spew. There is a lot of messaging activity happening inside of a Cocoa program. Adam came up with a clever way to limit the tracing to a particular object, and added a way to turn this tracing on and off from within the program. In essence, Adam’s test program told DTrace to start emitting the method trace at a well-defined point in the overall program’s execution, and then told DTrace to stop, because there would be no more interesting activity happening.

He added a function which would be the tracing toggle:

void observeObject (id objectToWatch) { }

It’s just an empty function. When you want to start tracing the messages sent to an object, call it in your code:

observeObject (self.gronkulator);

When you want to stop tracing, pass nil:

observeObject (nil);

And then run the program under the auspices of Dtrace with this script (available at this gist)

/* run with * # dtrace -qs watch-array.d -c ./array */ int64_t observedObject; pid$target::observeObject:entry { printf ("observing object: %p ", arg0); observedObject = arg0; } objc$target:::entry /arg0 == observedObject/ { printf("%s %s ", probemod, probefunc); /* uncomment to print stack: * ustack(); */ }

So, how does this work? There’s a global variable, observedObject, that holds the address of the object that you want to trace messages to. It defaults to zero.

When the Objective-C program calls observeObject(), the first clause gets invoked. It uses the pid provider to attach some actions that get run when observeObject() is called. It snarfs the first (and only argument), and stashes it in the observedObject global. Its work is done.

The second clause says to do stuff on every single Objective-C message send. Every single one. Having the actions run on every message would be overkill, plus would probably overwhelm the DTrace machinery in the kernel and cause it to drop data. The /arg0 == observedObject/ predicate looks at arg0, the receiver of the message, and checks to see if it’s the same as the object that needs the tracing. If it is, print out the module (class) and function (method name) of the sent message. Otherwise do nothing.

Here’s a program:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h> // clang -g -fobjc-arc -framework Foundation -o array array.m void observeObject (id objectToWatch) { // Just a stub to give DTrace something to hook in to. } int main (void) { @autoreleasepool { NSArray *thing1 = @[ @1, @2, @3, @4]; observeObject (thing1); [thing1 enumerateObjectsUsingBlock: ^(id thing, NSUInteger index, BOOL *whoa) { NSLog (@"Saw %@", thing); }]; observeObject (nil); NSLog (@"it's got %ld elements", thing1.count); } return 0; } // main

It makes an array, starts the observation, and then enumerates. The observation gets turned off, and the array is used again.

Here’s the output:

# dtrace -qs watch-array.d -c ./array dtrace: script 'watch-array.d' matched 11413 probes 2013-02-20 19:36:26.645 array[7674:803] Saw 1 2013-02-20 19:36:26.648 array[7674:803] Saw 2 2013-02-20 19:36:26.649 array[7674:803] Saw 3 2013-02-20 19:36:26.649 array[7674:803] Saw 4 2013-02-20 19:36:26.650 array[7674:803] it's got 4 elements dtrace: pid 7674 has exited observing object: 7fdfeac14890 NSArray -enumerateObjectsUsingBlock: NSArray -enumerateObjectsWithOptions:usingBlock: __NSArrayI -count __NSArrayI -count __NSArrayI -countByEnumeratingWithState:objects:count: __NSArrayI -countByEnumeratingWithState:objects:count: observing object: 0

A lot of interesting stuff happening here. You can see the originalenumerateObjectsUsingBlock call, which turns around and callsenumerateObjectsWithOptions Those are NSArray methods. Then there’s some__NSArrayI classes, most likely the actual implementation of Immutable arrays. It does some work, and then the observation stops.

THE NILS ARE ALIVE

One interesting feature of Objective-C is that messages to nil are totally legal. They’re fundamentally no-ops so you don’t have to keep checking for nil all over your code. You can sometimes eliminate whole classes of if statements by using an object to do some work, and then put a nil object in its place to not do some work. It’d be kind of cool to see how often real code uses message sends to nil.

Objective-C messages are actually implemented by a C function called objc_msgSend. Its first argument is the receiver of the object. You can tell DTrace to look at that first argument and log a stack trace when it’s zero. The pid provider lets you do that:

pid$target::objc_msgSend:entry /arg0 == 0/ { ustack (5); }

Run it against TextEdit:

# dtrace -s nilsends.d -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEditAnd you’ll get a lot of stuff, like

0 24327 objc_msgSend:entry libobjc.A.dylib`objc_msgSend Foundation`-[NSURL(NSURLPathUtilities) URLByAppendingPathComponent:]+0xdc AppKit`persistentStateDirectoryURLForBundleID+0x104 AppKit`+[NSPersistentUIManager(NSCarbonMethods) copyPersistentCarbonWindowDictionariesForBundleID:]+0x74

Wouldn’t it be nice you could get a count of who sends messages to nil most often? Wouldn’t it be nice if we could aggregate some data and print it out when the tracing ends?

DTRACE AGGREGATES

Why yes you can. You can’t leave a DTrace discussion without talking about aggregates. An aggregates is a variable, similar to a DTrace associative array. They’re indexed by an arbitrary list of stuff, and the name is preceded by an at-sign. You use an aggregate like this:

@aggregateName[list, of, indexes] = function(expression);

function is something like count, min, max, avg, sum, and so on. Take a look at count:

@counts[probefunc] = count();

This will count the number of times a function is called. Here’s a one-liner to run against the array program from earlier that counts all the system calls made:

# dtrace -n 'syscall:::entry { @counts[probefunc] = count(); }' -c ./array

When the program ends it prints the a list of system calls and the number of times each one was called. It’s also handily sorted from smallest to largest:

... mmap 17 lseek 25 write_nocancel 26 getuid 29 workq_kernreturn 110 kevent 190 select 274

That’s a lot of system work for such a small program.

The other aggregate functions take arguments. You can use sum(expression) to accumulate the amount of data asked for in reads, system wide:

# dtrace -n 'syscall::read:entry { @read_amounts[execname] = sum(arg2); }'

Run that command and then interrupt it with control-C. It’ll print out the aggregate:

configd 33152 Scrivener 104393 zip 119508 Mailplane 294912 Activity Monito 305703 mdworker 1095182 Terminal 1772088 Safari 2005992 mds 2658305 WebProcess 3367064 fseventsd 3675047

?Getting back to things Objective-C, you can see who is making the most message sends to nil. Here’s another script (nilsends-2.d):

pid$target::objc_msgSend:entry /arg0 == 0/ { @stacks[ustack(5)] = count(); } END { trunc (@stacks, 20); }

Three cool things: the END provider, whose full name is dtrace:::END, has its actions run when the script exits (there’s a corresponding BEGIN provider too). You can see the @stacksaggregate – it’s using the call stack as the index. This means that common stacks will have a higher count. When the script ends, the aggregate gets truncated to the highest 20 values, and then is automatically printed out. Here’s a run with TextEdit, letting it launch, and then immediately quitting.

# dtrace -s nilsends-2.d -c /Applications/TextEdit.app/Contents/MacOS/TextEditIt has these stacks at the end of the output:?

libobjc.A.dylib`objc_msgSend AppKit`-[NSView convertRect:toView:]+0x3e AppKit`-[NSWindow _viewIsInContentBorder:]+0x5f AppKit`-[NSCell(NSCellBackgroundStyleCompatibility) _externalContextSeemsLikelyToBeRaised]+0xf5 AppKit`-[NSCell(NSCellBackgroundStyleCompatibility) _initialBackgroundStyleCompatibilityGuess]+0x48 206 libobjc.A.dylib`objc_msgSend AppKit`+[NSTextFinder _setFindIndicatorNeedsUpdateForView:]+0x32 AppKit`-[NSView _invalidateGStatesForTree]+0x38a CoreFoundation`CFArrayApplyFunction+0x44 AppKit`-[NSView _invalidateGStatesForTree]+0x2a2 208 libobjc.A.dylib`objc_msgSend AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _titlePathForUserKeyEquivalents]+0x1b2 AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _fetchFreshUserKeyEquivalentInfo]+0x66 AppKit`-[NSMenuItem userKeyEquivalent]+0x4f AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _desiredKeyEquivalent]+0x3a 244 libobjc.A.dylib`objc_msgSend AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _titlePathForUserKeyEquivalents]+0xed AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _fetchFreshUserKeyEquivalentInfo]+0x66 AppKit`-[NSMenuItem userKeyEquivalent]+0x4f AppKit`-[NSMenuItem _desiredKeyEquivalent]+0x3a 244

So NSMenuItem is doing the most nil message sends (244 times from two different locations inside of _titlePathForUserKeyEqivalents), and then NSTextFinder.

FUN THINGS TO TRY

Take the listing of all the objc probes in TextEdit, and search for the term “hack”. See if you can find some cool sounding classes or methods, and then see if they’re documented.

Put probes on mouseDown / mouseUp, and use aggregates to see how many of those events happen in a typical run of your program.

You can index aggregates by more than one value. Adapt the system call counting script to also record the executable name. You’d index @counts by execname and probefunc.

Ask Uncle Google about printa(), which lets you print out DTrace aggregates in a prettier format. Also look around for the quantize() aggregate function, which will build a histogram of the values it sees, and output a glorious ASCII chart.

THAT’S ALL FOLKS

So you can see, there’s a lot of power contained in DTrace for investigating things in Objective-C land as there are looking programs with the pid provider or looking at system calls. Hopefully this has demystified enough of DTrace to let you pull it out of your toolbox and amaze your friends.

===========================================================

Part 4

I lied. Sorry. I thought this dive into DTrace would be a three-parter, but here’s a part 4, on static probes, suggested in a comment by Chris last month.

You can go a long way with the built in DTrace providers, like the syscall, pid, and 4 providers. But sometimes it would be nice to examine program behavior with a higher-level semantic meaning. That’s just a fancy way of saying “I want to know what this program is doing” without having to tease it out of sequence of function or method calls.

There’s not really any way to get that information from DTrace directly, so your program (or library) needs a way to tell DTrace “Hey, the user clicked on Finland” or “Hey, CoreData just had to fetch 30 bazillion objects.” Luckily there’s a way to do that, otherwise this would be a very short posting. It’s also surprisingly easy.

HEAVY METAL

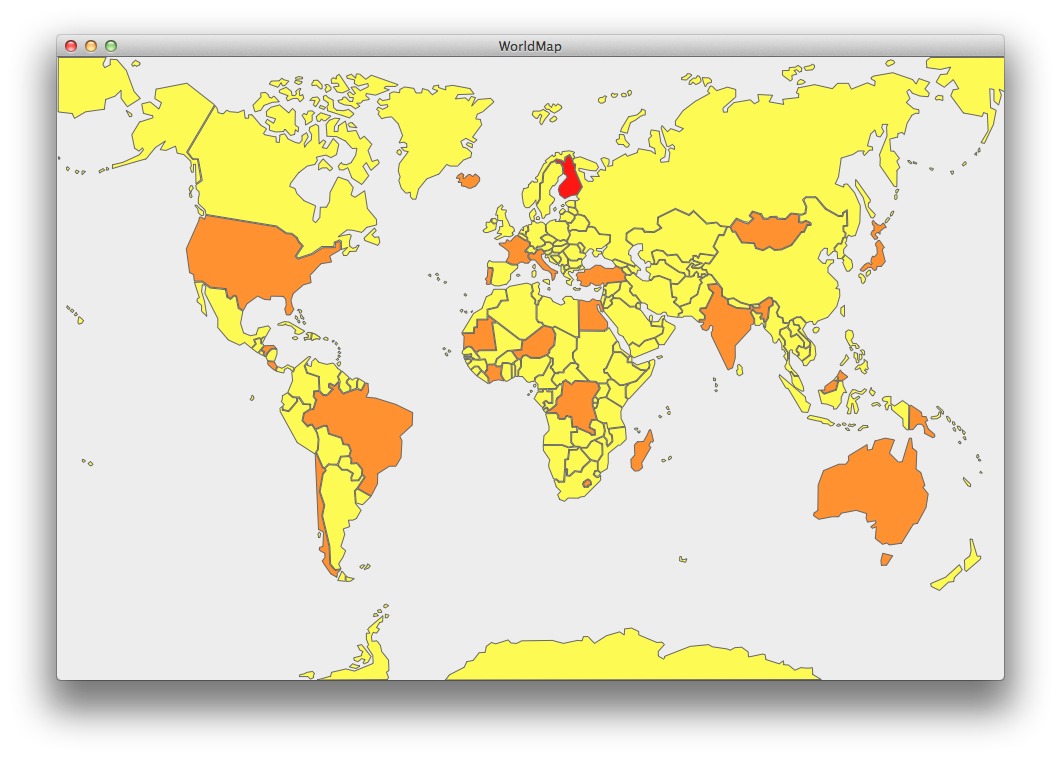

Last year I used a little program that showed off delegation and datasources using a world map:

You can get the code from the WorldMapView github.

Wouldn’t It Be Cool to know what countries the user is clicking on most? As it stands now, you can’t really do that with DTrace. Sure, you can use the objc provider to catch mouse downs or calls to the -selectedCountryCode delegate method, but the program uses NSStrings for the country codes that are passed around, and you can’t call arbitrary Objective-C methods (such as UTF8String) from inside of DTrace to see what the string actually contains.

One way to do it is to make your own static probes. These are functions you explicitly call inside your program or library that tell DTrace “Hey, if you’re interested in country-clicking, someone just clicked on FI.” You can then put a DTrace probe on country-clicks, and all the other data available in DTrace is at your disposal like stack traces and timestamps. You can ask questions such as “What was the average time between clicks on Madagascar before the borders were closed?”

STEP 1 : DESCRIBE YOUR PROBES

Make a .d file that describes the probes you’re adding. The one for WorldMap is pretty simple:

provider BNRWorldMap { probe country_clicked (char *); };

The provider is called BNRWorldMap, and is suffixed with a process number when used in a DTrace script. The probe’s name is country_clicked. Its arg0 will be the address of a C string of the country code that was clicked on. You can provide any arguments you want. Integer-compatible values are passed directly, and you’ll need to use a copyin action for others (such as getting the C string for the clicked-on country code). You can have any number of individual probes here.

In a DTrace script you’d use it like this:

# dtrace -n 'BNRWorldMap$target:::country_clicked' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap dtrace: description 'BNRWorldMap$target:::country_clicked' matched 1 probe CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 1 166855 -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:]:country_clicked 1 166855 -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:]:country_clicked 2 166855 -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:]:country_clicked 1 166855 -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:]:country_clicked

If you wanted to get at the actual country code, you’d use copyinstr, passing it arg0, to get the C string copied to kernel space as described in part 1.

STEP 2: MAKE THE HEADER

You can’t include that .d script directly in Objective-C code. You’ll need to generate a header file that you can #import. Xcode will do that automatically if you drag the .d file into your project – things will Just Work. If you want to make a header yourself you can tell dtrace to do it:

% dtrace -h -s WorldMapProbes.d

You can then look at WorldMapProbes.h and see what it’s doing. It’s kind of cool poking around in there to see what’s going on. dtrace generates two macros for each probe specified in the .d file:

BNRWORLDMAP_COUNTRY_CLICKED_ENABLED returns true if DTrace has been commanded to monitor country_clicked probes in this process. You can use this to gate any expensive work you might want to do when constructing the data you’ll be passing back to DTrace, but otherwise wouldn’t be necessary.

BNRWORLDMAP_COUNTRY_CLICKED is what you call to tell DTrace that something interesting happened. In this case, a country getting clicked. You pass it the parameters you promised in the WorldMapProbes.d file.

Using them is very straightforward:

if (BNRWORLDMAP_COUNTRY_CLICKED_ENABLED()) { BNRWORLDMAP_COUNTRY_CLICKED (countryCode.UTF8String); }

You don’t have to check if the probe is enabled, but it’s generally a good idea. Notice that the UTF8 string is extracted from the NSString because DTrace doesn’t grok NSStrings.

STEP 3: THERE IS NO STEP 3

Now you can build and run your program and see what you’ve created. Get a listing of the probes just to make sure everything got set up correctly:

# dtrace -l -n 'BNRWorldMap$target:::' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 11892 BNRWorldMap51759 WorldMap -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:] country_clicked

You can see that you provide the provider and name portion of the probe description, and DTrace fills in the module (the program name) and the function (whereBNRWORLDMAP_COUNTRY_CLICKED is called). You can put the same probe in different functions or methods and have different specific probe points you can look at. I tossed a call into -isFlipped just for demonstration:

# dtrace -l -n 'BNRWorldMap$target:::' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap ID PROVIDER MODULE FUNCTION NAME 11892 BNRWorldMap51787 WorldMap -[BNRWorldMapView isFlipped] country_clicked 11893 BNRWorldMap51787 WorldMap -[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:] country_clicked

Peer at arg0 and see what’s clicked:

# dtrace -q -n 'BNRWorldMap$target:::country_clicked { printf("clicked in %s ", copyinstr(arg0)); }' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap clicked in US clicked in FR clicked in CN clicked in AU clicked in AU clicked in US

OONGAWA!

OK, so that’s not much better than caveman debugging that you can turn on or off at runtime. You could get the same info with an NSLog inside of -mouseDown. How about doing something you can’t duplicate with NSLog? An interesting question might be “What are the most commonly clicked countries over the run of the program?”, a good use of DTrace aggregation. Here’s a script:

BNRWorldMap$target:::country_clicked { @clicks[copyinstr(arg0)] = count(); }

Every time a country is clicked, the action body grabs the country code from arg0 and indexes an aggregate with it that is maintaining a count of clicks. (Refer back to part 3 if this sounds like gibberish.)

You can run it as a one-liner, click around the map, then interrupt dtrace with a control-C to get the output:

# dtrace -q -n 'BNRWorldMap$target:::country_clicked { @clicks[copyinstr(arg0)] = count(); }' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap ^C BR 1 FR 1 IT 1 SE 2 AU 3 US 3 CN 6 FI 13

BONUS: OTHER STATIC PROBES

One of the true joys of DTrace is serendipitous discovery of nerdy tools. You can list all of the probes, including the static probes, with a command like:

# dtrace -l ':::' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap > probes.txtThis produces about 185,000 lines of output for me, showing static probes for many applications in the system. I boiled down the providers inside of WorldMap:

BNRWorldMap Cocoa_Autorelease Cocoa_Layout CoreData CoreImage HALC_IO NSApplication NSTrackingArea RemoteViewServices cache codesign garbage_collection magmalloc objc_runtime opencl_api plockstat security_debug security_exception syspolicy

Some really cool stuff. Like with Cocoa autolayout (51038 is the process ID of the WorldMap program I took this listing from):

17016 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit ConstraintDidPerformInitialSetup constraint_lifecycle 17017 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit -[NSLayoutConstraint setPriority:] constraint_lifecycle 17018 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit -[NSLayoutConstraint _setIdentifier:] constraint_lifecycle 17019 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit -[NSLayoutConstraint _setSymbolicConstant:constant:] constraint_lifecycle 17020 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit -[NSLayoutConstraint _addToEngine:roundingAdjustment:mutuallyExclusiveConstraints:] constraint_lifecycle 17021 Cocoa_Layout51038 AppKit -[NSLayoutConstraint _removeFromEngine:] constraint_lifecycle

So you could put a probe on constraint_lifecycle and see when its priority changes, or when it gets added to the layout engine.

There’s also probes on NSTracking area, to see when tracking areas are added, created, enabled and disabled, and removed.

objc_runtime can let you attach probes on exception throwing:

16007 objc_runtime51038 libobjc.A.dylib objc_exception_rethrow objc_exception_rethrow 16008 objc_runtime51038 libobjc.A.dylib objc_exception_throw objc_exception_throw

You could use ustack() to record the stack traces when something bad happens. Throwing a quick

[@"" stringByAppendingString: nil];

into WorldMapView‘s -mouseDown forces an exception. Running with this command

# dtrace -n '<strong>objc_runtime$target</strong>::: { ustack(); } ' -c ./WorldMap.app/Contents/MacOS/WorldMap

gives this stack from DTrace:

CPU ID FUNCTION:NAME 0 10864 objc_exception_throw:objc_exception_throw libobjc.A.dylib`objc_exception_throw+0x12f CoreFoundation`+[NSException raise:format:arguments:]+0x6a CoreFoundation`+[NSException raise:format:]+0x74 Foundation`-[NSString stringByAppendingString:]+0x5b WorldMap`-[BNRWorldMapView mouseDown:]+0x85 AppKit`-[NSWindow sendEvent:]+0x18a2 AppKit`-[NSApplication sendEvent:]+0x15d9 AppKit`-[NSApplication run]+0x22b AppKit`NSApplicationMain+0x363 WorldMap`main+0x22 WorldMap`start+0x34 WorldMap`0x1

You don’t get file and line goodness, but sometimes this might be all the information you need for tracking down weird in-the-field problems.

Finally, CoreData provides a number of probes related to faulting:

BeginFault EndFault BeginFaultCacheMiss EndFaultCacheMiss BeginFetch EndFetch BeginRelationshipCacheMiss EndRelationshipCacheMiss BeginRelationshipFault EndRelationshipFault BeginSave EndSave

Which you can experiment with to watch your CoreData behavior. This is what the CoreData instrument is based on, by the way.

THAT’S ALL FOLKS, FOR REAL

I was actually shocked and amazed at how easy it was to make custom DTrace probes. I had put off learning about them for years assuming it’d time consuming figuring them out. Can’t get much easier than building a small D script, dropping it into Xcode, and invoking one of the generated macros.