cat src/main.rs fn main() { let x= String::from("42"); let y=x; println!("value of x :{}",x); }

cargo build Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own) warning: unused variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:4:9 | 4 | let y=x; | ^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_y` | = note: `#[warn(unused_variables)]` on by default error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `x` --> src/main.rs:5:31 | 3 | let x= String::from("42"); | - move occurs because `x` has type `std::string::String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait 4 | let y=x; | - value moved here 5 | println!("value of x :{}",x); | ^ value borrowed here after move error: aborting due to previous error; 1 warning emitted For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0382`. error: could not compile `own`. To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

fn main() { let x= String::from("42"); let y=&x; println!("value of x :{}",x); }

cargo run warning: unused variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:4:9 | 4 | let y=&x; | ^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_y` | = note: `#[warn(unused_variables)]` on by default warning: 1 warning emitted Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.01s Running `target/debug/own` value of x :42

cat src/main.rs fn main() { let x= String::from("hello world"); let y=&x; println!("value of x :{}",x); }

[root@bogon own]# cargo build Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own) warning: unused variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:4:9 | 4 | let y=&x; | ^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_y` | = note: `#[warn(unused_variables)]` on by default warning: 1 warning emitted Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.44s [root@bogon own]# cargo run warning: unused variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:4:9 | 4 | let y=&x; | ^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_y` | = note: `#[warn(unused_variables)]` on by default warning: 1 warning emitted Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.01s Running `target/debug/own` value of x :hello world [root@bogon own]

cat src/main.rs fn main() { let y : i32; { let x=1; let y=&x; } println!("value of y :{}",y); }

cargo build Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own2) warning: unused variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:6:9 | 6 | let y=&x; | ^ help: if this is intentional, prefix it with an underscore: `_y` | = note: `#[warn(unused_variables)]` on by default error[E0381]: borrow of possibly-uninitialized variable: `y` --> src/main.rs:8:31 | 8 | println!("value of y :{}",y); | ^ use of possibly-uninitialized `y` error: aborting due to previous error; 1 warning emitted For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0381`. error: could not compile `own`. To learn more, run the command again with --verbose. [root@bogon own2]# cat src/main.rs fn main() { let y : i32; { let x=1; let y=&x; } println!("value of y :{}",y); }

fn push(vec: &mut Vec<u32>) { vec.push(1); } fn main(){ let mut vec = vec![0, 1, 3, 5]; push(&mut vec); println!("{:?}", vec); }

cargo build Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own3) Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.54s [root@bogon own3]# cargo run Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.01s Running `target/debug/own` [0, 1, 3, 5, 1]

fn push(vec: mut Vec<u32>) { vec.push(1); } fn main(){ let mut vec = vec![0, 1, 3, 5]; push(mut vec); println!("{:?}", vec); }

[root@bogon own3]# cargo build

Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own3)

error: expected type, found keyword `mut`

--> src/main.rs:1:14

|

1 | fn push(vec: mut Vec<u32>) {

| ^^^ expected type

error: expected expression, found keyword `mut`

--> src/main.rs:7:10

|

7 | push(mut vec);

| ^^^ expected expression

error[E0423]: expected value, found macro `vec`

--> src/main.rs:2:7

|

2 | vec.push(1);

| ^^^ not a value

|

help: use `!` to invoke the macro

|

2 | vec!.push(1);

| ^

error: aborting due to 3 previous errors

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0423`.

error: could not compile `own`.

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

[root@bogon own3]#

struct Foo { x: &i32, } fn main() { let y = &5; let f = Foo { x: y }; println!("{}", f.x); }

Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own4) error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier --> src/main.rs:2:10 | 2 | x: &i32, | ^ expected named lifetime parameter | help: consider introducing a named lifetime parameter | 1 | struct Foo<'a> { 2 | x: &'a i32, | error: aborting due to previous error For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0106`. error: could not compile `own`. To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

struct Foo<'val> { x: &'val i32, } fn main() { let y = &5; let f = Foo { x: y }; println!("{}", f.x); }

cargo build Compiling own v0.1.0 (/data2/rust/own5) Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.39s [root@bogon own5]# cargo run Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.01s Running `target/debug/own` 5

语义模型

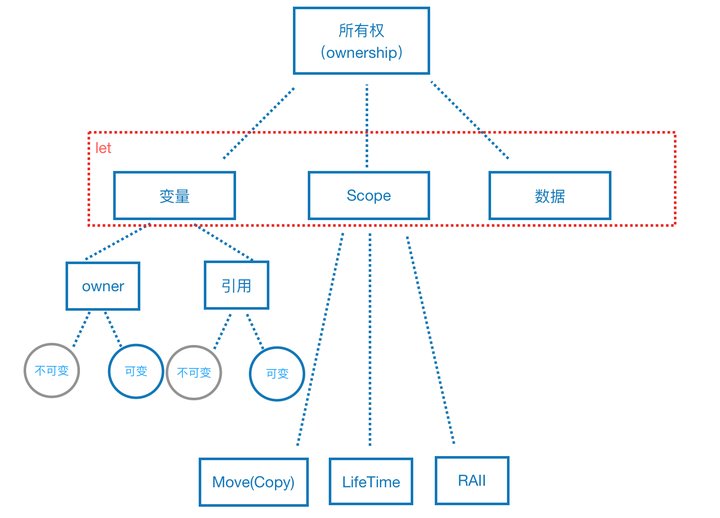

什么叫语义模型?语义,顾名思义,是指语言的含义。我们在学习一个新概念的时候,首先就要搞明白它的语义。而语义模型,是指语义构建的心智模型,因为概念点不是孤立存在的,彼此之间必然有紧密的联系,我们通过挖掘其语义之间的关联规则,在你的认知中形成一颗“语义树”,这样的理解才是通透的。所有权的“语义树”,如下图所示:

上图中的语义树,主要是想表达下面几层意思:

- 所有权是有好多个概念系统性组成的一个整体概念。

- let绑定,绑定了什么?变量 + 作用域 + 数据(内存)。

- move、lifetime、RAII都是和作用域相关的,所以想理解它们就先要理解作用域。

所有权

所有权,顾名思义,至少应该包含两个对象:“所有者”和“所有物”。在Rust中,“所有者”就是变量,“所有物”是数据,抽象来说,就是指某一片内存。let关键字,允许你绑定“所有者”和“所有物”,比如下面代码:

let num = String::from("42");let关键字,让num绑定了42,那么可以说,num拥有42的所有权。但这个所有权,是有范围限制的,这个范围就是作用域(scope),准确来说,应该叫拥有域(owner scope)。换句话说,num在当前作用域下,拥有42的所有权。如果它要进入别的作用域,就必须交出所有权。比如下面的代码:

let num = String::from("42");

let num2 = num;let关键字会开启一个隐藏作用域,我们可以借助于MIR来查看,编译这两行代码,查看其MIR:

scope 1 {

let _1: std::string::String; // "num" in scope 1 at <anon>:4:8: 4:11

scope 2 {

let _2: std::string::String; // "num2" in scope 2 at <anon>:5:8: 5:12

}

}Scope 1就是num所在的作用域,scope 2是num2所在的作用域。当你此时想像下面这样使用num的时候:

let num = String::from("42");

let num2 = num;

println!("{:?}", num);编译器会报错:error[E0382]: use of moved value: `num`。因为num变量的所有权已经转移了。

移动(move)语义

移动,是指所有权的转移。什么时候所有权会转移呢?就是当变量切换作用域的时候,所谓移动,当然是从一个地方挪到另一个地方。其实你也可以这样认为,当变量切换到另一个作用域,它在当前作用域的绑定将会失效,它拥有的数据则会在另一个作用域被重新绑定。

但是对于实现了Copy Trait的类型来说,当移动发生的时候,它们可以Copy的副本代替自己去移动,而自身还保留着所有权。比如,Rust中的基本数字类型都默认实现了Copy Trait,比如下面示例:

let num = 42;

let num2 = num;

println!("{:?}", num);

此时,我们打印num,编译器不会报错。num已经move了,但是因为数字类型是默认实现Copy Trait,所以它move的是自身的副本,其所有权还在,并未发生转移,通过编译。不过需要注意的是,Rust 不允许自身或其任何部分实现了Drop trait 的类型使用Copy trait。

当move发生的时候,所有权被转移的变量,将会被释放。

作用域(Scope)

没有GC帮助我们自动管理内存,我们只能依赖所有权这套规则来手工管理内存,这就增加了我们的心智负担。而所有权的这套规则,是依赖于作用域的,所以我们需要对Rust中的作用域有一定了解。

我们在之前的描述中已经见过了隐式作用域,也就是在当前作用域中由let开启的作用域。在Rust中,也有一些特殊的宏,比如println!(),也会产生一个默认的scope,并且会隐式借用变量。除此之外,更明显的作用域 范围则是函数,也就是说,一个函数本身,就是一个显式的作用域。你也可以使用一对花括号({})来创建显式的作用域。

除此之外,一个函数本身就显式的开辟了一个独立的作用域。比如:

fn sum(a: u32, b: u32) -> u32 {

a + b

}

fn main(){

let a = 1;

let b = 2;

sum(a, b);

}

上面的代码中,当调用sum函数的时候,a和b当作参数传递过去,此时就会发生所有权move的行为,但是因为a和b都是基本数据类型,实现了Copy Trait,所以它们的所有权没有被转移。如果换了是没有实现Copy Trait的变量,所有权就会被转移。

作用域在Rust中的作用就是制造一个边界,这个边界是所有权的边界。变量走出其所在作用域,所有权会move。如果不想让所有权move,则可以使用“引用”来“出借”变量,而此时作用域的作用就是保证被“借用”的变量准确归还。

引用和借用

有的时候,我们并不想让变量的所有权转移,比如,我写一个函数,该函数只是给某个数组插入一个固定的值:

fn push(vec: &mut Vec<u32>) {

vec.push(1);

}

fn main(){

let mut vec = vec![0, 1, 3, 5];

push(&mut vec);

println!("{:?}", vec);

}

此时,我们把数组vec传给push函数,就不希望把所有权转移,所以,只需要传入一个可变引用&mut vec,因为我们需要修改vec,这样push函数就得了vec变量的可变借用,让我们去修改。push函数修改完,会将借用的所有权归还给vec,然后println!函数就可以顺利使用vec来输出打印。

引用非常方便我们使用,但是如果滥用的话,会引起安全问题,比如悬垂指针。看下面示例:

let r;

{

let a = 1;

r = &a;

}

println!("{}", r);上面代码中,当a离开作用域的时候会被释放,但此时r还持有一个a的借用,编译器中的借用检查器就会告诉你:`a` does not live long enough。翻译过来就是:`a`活的不够久。这代表着a的生命周期太短,而无法借用给r,否则&a就指向了一个曾经存在但现在已不再存在的对象,这就是悬垂指针,也有人将其称为野指针。

生命周期

上面的示例中,是在同一个函数作用域下,编译器可以识别出生命周期的问题,但是当我们在函数之间传递引用的时候,编译器就很难自动识别出这些问题了,所以Rust要求我们为这些引用显式的指定生命周期标记,如果你不指定生命周期标记,那么编译器将会“鞭策”你。

struct Foo {

x: &i32,

}

fn main() {

let y = &5;

let f = Foo { x: y };

println!("{}", f.x);

}

上面这段代码,编译器会提示你:missing lifetime specifier。这是因为,y这个借用被传递到了 let f = Foo { x: y }所在作用域中。所以需要确保借用y活得比Foo结构体实例长才行,否则,如果借用y被提前释放,Foo结构体实例就会造成悬垂指针了。所以我们需要为其增加生命周期标记:

struct Foo<'a> {

x: &'a i32,

}

fn main() {

let y = &5;

let f = Foo { x: y };

println!("{}", f.x);

}

加上生命周期标记以后,编译器中的借用检查器就会帮助我们自动比对参数变量的作用域长度,从而确保内存安全。

再来看一个例子:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

fn main() {

let a = "hello";

let result;

{

let b = String::from("world");

result = longest(a, b.as_str());

}

println!("The longest string is {}", result);

}

此段代码,编译器会报错:`b` does not live long enough。这是因为result在外部作用域定义的,result的生命周期是和main函数一样长的,也就是说,在main函数作用域结束之前,result都必须存活。而此时,变量b在花括号定义的作用域中,出了作用域b就会被释放。而根据longest函数签名中的生命周期标注,参数b的生命周期必须和返回值的生命周期一致,所以,借用检查器果断的判断出`b` does not live long enough。

“显式的指定”,这是Rust的设计哲学之一。这对于新手,尤其是习惯了动态语言的人来说,可能是一个心智负担。显式的指定方便了编译器,但是对于程序员来说略显繁琐。不过为了安全考虑,我们就欣然接受这套规则吧。