序

像其他大型软件一样,Linux制订了一套编码风格,对代码的格式、风格和布局做出了规定。我写这篇的目的也就是希望大家能够从中借鉴,有利于大家提高编程效率。

像Linux内核这样大型软件中,涉及许许多多的开发者,故它的编码风格也很有参考价值。

括号

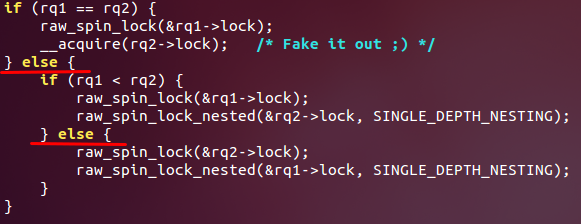

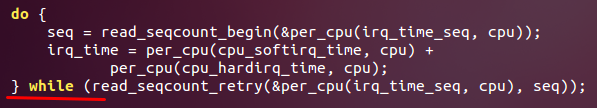

1、左括号紧跟在语句的最后,与语句在相同的一行。而右括号要另起一行,作为该行的第一个字符。

2、如果接下来的部分是相同语句的一部分,那么右括号就不单独占一行。

3、还有

4、函数采用以下的书写方式:

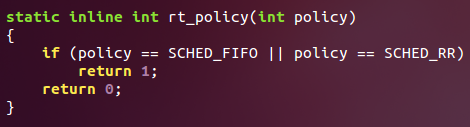

5、最后不需要一定使用括号的语句可以忽略它:

每行代码的长度

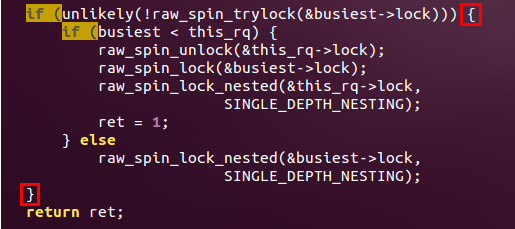

要尽可能地保证代码长度不超过80个字符,如果代码行超过80应该折到下一行。

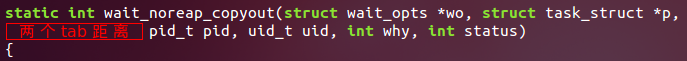

将参数分行输入,在开头简单地加入两个标准tab:

命名规范

名称中不允许使用混合的大小写字符。

局部变量如果能够清楚地表明它的用途,那么选取idx甚至是i这样的名称都是可行的。而像theLoopIndex这样冗长反复的名字不在接受之列。——匈牙利命名法(在变量名称中加入变量的类别)危害极大。

函数

根据经验函数的代码长度不应该超过两屏,局部变量不应该超过十个。

1、一个函数应该功能单一并且实现精准。2、将一个函数分解成一些更短小的函数的组合不会带来危害。——如果你担心函数调用导致的开销,可以使用inline关键字。

注释

一般情况下,注释的目的是描述你的代码要做什么和为什么要做,而不是具体通过什么方式实现的。怎么实现应该由代码本身展现。

注释不应该包含谁写了那个函数,修改日期和其他那些琐碎而无实际意义的内容。这些信息应该集中在文件最开头地方。

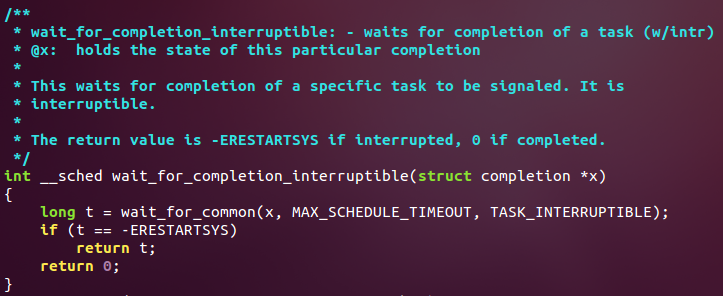

内核中一条注释看起来如下:

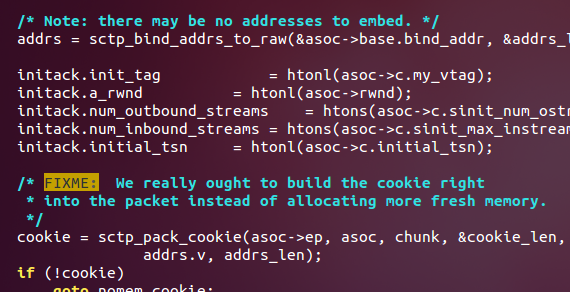

重要信息常常以“XXX:”开头,而bug通常以“FIXME"开头,就像:

总结

希望这篇博客对大家有所帮助!

更详尽的内容,请看"Linux 内核代码规范原文"

Linus 内部代码规范原文

Linus 内部代码规范原文

1 Linux kernel coding style 2 3 This is a short document describing the preferred coding style for the 4 linux kernel. Coding style is very personal, and I won't _force_ my 5 views on anybody, but this is what goes for anything that I have to be 6 able to maintain, and I'd prefer it for most other things too. Please 7 at least consider the points made here. 8 9 First off, I'd suggest printing out a copy of the GNU coding standards, 10 and NOT read it. Burn them, it's a great symbolic gesture. 11 12 Anyway, here goes: 13 14 15 Chapter 1: Indentation 16 17 Tabs are 8 characters, and thus indentations are also 8 characters. 18 There are heretic movements that try to make indentations 4 (or even 2!) 19 characters deep, and that is akin to trying to define the value of PI to 20 be 3. 21 22 Rationale: The whole idea behind indentation is to clearly define where 23 a block of control starts and ends. Especially when you've been looking 24 at your screen for 20 straight hours, you'll find it a lot easier to see 25 how the indentation works if you have large indentations. 26 27 Now, some people will claim that having 8-character indentations makes 28 the code move too far to the right, and makes it hard to read on a 29 80-character terminal screen. The answer to that is that if you need 30 more than 3 levels of indentation, you're screwed anyway, and should fix 31 your program. 32 33 In short, 8-char indents make things easier to read, and have the added 34 benefit of warning you when you're nesting your functions too deep. 35 Heed that warning. 36 37 The preferred way to ease multiple indentation levels in a switch statement is 38 to align the "switch" and its subordinate "case" labels in the same column 39 instead of "double-indenting" the "case" labels. E.g.: 40 41 switch (suffix) { 42 case 'G': 43 case 'g': 44 mem <<= 30; 45 break; 46 case 'M': 47 case 'm': 48 mem <<= 20; 49 break; 50 case 'K': 51 case 'k': 52 mem <<= 10; 53 /* fall through */ 54 default: 55 break; 56 } 57 58 59 Don't put multiple statements on a single line unless you have 60 something to hide: 61 62 if (condition) do_this; 63 do_something_everytime; 64 65 Don't put multiple assignments on a single line either. Kernel coding style 66 is super simple. Avoid tricky expressions. 67 68 Outside of comments, documentation and except in Kconfig, spaces are never 69 used for indentation, and the above example is deliberately broken. 70 71 Get a decent editor and don't leave whitespace at the end of lines. 72 73 74 Chapter 2: Breaking long lines and strings 75 76 Coding style is all about readability and maintainability using commonly 77 available tools. 78 79 The limit on the length of lines is 80 columns and this is a strongly 80 preferred limit. 81 82 Statements longer than 80 columns will be broken into sensible chunks, unless 83 exceeding 80 columns significantly increases readability and does not hide 84 information. Descendants are always substantially shorter than the parent and 85 are placed substantially to the right. The same applies to function headers 86 with a long argument list. However, never break user-visible strings such as 87 printk messages, because that breaks the ability to grep for them. 88 89 90 Chapter 3: Placing Braces and Spaces 91 92 The other issue that always comes up in C styling is the placement of 93 braces. Unlike the indent size, there are few technical reasons to 94 choose one placement strategy over the other, but the preferred way, as 95 shown to us by the prophets Kernighan and Ritchie, is to put the opening 96 brace last on the line, and put the closing brace first, thusly: 97 98 if (x is true) { 99 we do y 100 } 101 102 This applies to all non-function statement blocks (if, switch, for, 103 while, do). E.g.: 104 105 switch (action) { 106 case KOBJ_ADD: 107 return "add"; 108 case KOBJ_REMOVE: 109 return "remove"; 110 case KOBJ_CHANGE: 111 return "change"; 112 default: 113 return NULL; 114 } 115 116 However, there is one special case, namely functions: they have the 117 opening brace at the beginning of the next line, thus: 118 119 int function(int x) 120 { 121 body of function 122 } 123 124 Heretic people all over the world have claimed that this inconsistency 125 is ... well ... inconsistent, but all right-thinking people know that 126 (a) K&R are _right_ and (b) K&R are right. Besides, functions are 127 special anyway (you can't nest them in C). 128 129 Note that the closing brace is empty on a line of its own, _except_ in 130 the cases where it is followed by a continuation of the same statement, 131 ie a "while" in a do-statement or an "else" in an if-statement, like 132 this: 133 134 do { 135 body of do-loop 136 } while (condition); 137 138 and 139 140 if (x == y) { 141 .. 142 } else if (x > y) { 143 ... 144 } else { 145 .... 146 } 147 148 Rationale: K&R. 149 150 Also, note that this brace-placement also minimizes the number of empty 151 (or almost empty) lines, without any loss of readability. Thus, as the 152 supply of new-lines on your screen is not a renewable resource (think 153 25-line terminal screens here), you have more empty lines to put 154 comments on. 155 156 Do not unnecessarily use braces where a single statement will do. 157 158 if (condition) 159 action(); 160 161 and 162 163 if (condition) 164 do_this(); 165 else 166 do_that(); 167 168 This does not apply if only one branch of a conditional statement is a single 169 statement; in the latter case use braces in both branches: 170 171 if (condition) { 172 do_this(); 173 do_that(); 174 } else { 175 otherwise(); 176 } 177 178 3.1: Spaces 179 180 Linux kernel style for use of spaces depends (mostly) on 181 function-versus-keyword usage. Use a space after (most) keywords. The 182 notable exceptions are sizeof, typeof, alignof, and __attribute__, which look 183 somewhat like functions (and are usually used with parentheses in Linux, 184 although they are not required in the language, as in: "sizeof info" after 185 "struct fileinfo info;" is declared). 186 187 So use a space after these keywords: 188 if, switch, case, for, do, while 189 but not with sizeof, typeof, alignof, or __attribute__. E.g., 190 s = sizeof(struct file); 191 192 Do not add spaces around (inside) parenthesized expressions. This example is 193 *bad*: 194 195 s = sizeof( struct file ); 196 197 When declaring pointer data or a function that returns a pointer type, the 198 preferred use of '*' is adjacent to the data name or function name and not 199 adjacent to the type name. Examples: 200 201 char *linux_banner; 202 unsigned long long memparse(char *ptr, char **retptr); 203 char *match_strdup(substring_t *s); 204 205 Use one space around (on each side of) most binary and ternary operators, 206 such as any of these: 207 208 = + - < > * / % | & ^ <= >= == != ? : 209 210 but no space after unary operators: 211 & * + - ~ ! sizeof typeof alignof __attribute__ defined 212 213 no space before the postfix increment & decrement unary operators: 214 ++ -- 215 216 no space after the prefix increment & decrement unary operators: 217 ++ -- 218 219 and no space around the '.' and "->" structure member operators. 220 221 Do not leave trailing whitespace at the ends of lines. Some editors with 222 "smart" indentation will insert whitespace at the beginning of new lines as 223 appropriate, so you can start typing the next line of code right away. 224 However, some such editors do not remove the whitespace if you end up not 225 putting a line of code there, such as if you leave a blank line. As a result, 226 you end up with lines containing trailing whitespace. 227 228 Git will warn you about patches that introduce trailing whitespace, and can 229 optionally strip the trailing whitespace for you; however, if applying a series 230 of patches, this may make later patches in the series fail by changing their 231 context lines. 232 233 234 Chapter 4: Naming 235 236 C is a Spartan language, and so should your naming be. Unlike Modula-2 237 and Pascal programmers, C programmers do not use cute names like 238 ThisVariableIsATemporaryCounter. A C programmer would call that 239 variable "tmp", which is much easier to write, and not the least more 240 difficult to understand. 241 242 HOWEVER, while mixed-case names are frowned upon, descriptive names for 243 global variables are a must. To call a global function "foo" is a 244 shooting offense. 245 246 GLOBAL variables (to be used only if you _really_ need them) need to 247 have descriptive names, as do global functions. If you have a function 248 that counts the number of active users, you should call that 249 "count_active_users()" or similar, you should _not_ call it "cntusr()". 250 251 Encoding the type of a function into the name (so-called Hungarian 252 notation) is brain damaged - the compiler knows the types anyway and can 253 check those, and it only confuses the programmer. No wonder MicroSoft 254 makes buggy programs. 255 256 LOCAL variable names should be short, and to the point. If you have 257 some random integer loop counter, it should probably be called "i". 258 Calling it "loop_counter" is non-productive, if there is no chance of it 259 being mis-understood. Similarly, "tmp" can be just about any type of 260 variable that is used to hold a temporary value. 261 262 If you are afraid to mix up your local variable names, you have another 263 problem, which is called the function-growth-hormone-imbalance syndrome. 264 See chapter 6 (Functions). 265 266 267 Chapter 5: Typedefs 268 269 Please don't use things like "vps_t". 270 271 It's a _mistake_ to use typedef for structures and pointers. When you see a 272 273 vps_t a; 274 275 in the source, what does it mean? 276 277 In contrast, if it says 278 279 struct virtual_container *a; 280 281 you can actually tell what "a" is. 282 283 Lots of people think that typedefs "help readability". Not so. They are 284 useful only for: 285 286 (a) totally opaque objects (where the typedef is actively used to _hide_ 287 what the object is). 288 289 Example: "pte_t" etc. opaque objects that you can only access using 290 the proper accessor functions. 291 292 NOTE! Opaqueness and "accessor functions" are not good in themselves. 293 The reason we have them for things like pte_t etc. is that there 294 really is absolutely _zero_ portably accessible information there. 295 296 (b) Clear integer types, where the abstraction _helps_ avoid confusion 297 whether it is "int" or "long". 298 299 u8/u16/u32 are perfectly fine typedefs, although they fit into 300 category (d) better than here. 301 302 NOTE! Again - there needs to be a _reason_ for this. If something is 303 "unsigned long", then there's no reason to do 304 305 typedef unsigned long myflags_t; 306 307 but if there is a clear reason for why it under certain circumstances 308 might be an "unsigned int" and under other configurations might be 309 "unsigned long", then by all means go ahead and use a typedef. 310 311 (c) when you use sparse to literally create a _new_ type for 312 type-checking. 313 314 (d) New types which are identical to standard C99 types, in certain 315 exceptional circumstances. 316 317 Although it would only take a short amount of time for the eyes and 318 brain to become accustomed to the standard types like 'uint32_t', 319 some people object to their use anyway. 320 321 Therefore, the Linux-specific 'u8/u16/u32/u64' types and their 322 signed equivalents which are identical to standard types are 323 permitted -- although they are not mandatory in new code of your 324 own. 325 326 When editing existing code which already uses one or the other set 327 of types, you should conform to the existing choices in that code. 328 329 (e) Types safe for use in userspace. 330 331 In certain structures which are visible to userspace, we cannot 332 require C99 types and cannot use the 'u32' form above. Thus, we 333 use __u32 and similar types in all structures which are shared 334 with userspace. 335 336 Maybe there are other cases too, but the rule should basically be to NEVER 337 EVER use a typedef unless you can clearly match one of those rules. 338 339 In general, a pointer, or a struct that has elements that can reasonably 340 be directly accessed should _never_ be a typedef. 341 342 343 Chapter 6: Functions 344 345 Functions should be short and sweet, and do just one thing. They should 346 fit on one or two screenfuls of text (the ISO/ANSI screen size is 80x24, 347 as we all know), and do one thing and do that well. 348 349 The maximum length of a function is inversely proportional to the 350 complexity and indentation level of that function. So, if you have a 351 conceptually simple function that is just one long (but simple) 352 case-statement, where you have to do lots of small things for a lot of 353 different cases, it's OK to have a longer function. 354 355 However, if you have a complex function, and you suspect that a 356 less-than-gifted first-year high-school student might not even 357 understand what the function is all about, you should adhere to the 358 maximum limits all the more closely. Use helper functions with 359 descriptive names (you can ask the compiler to in-line them if you think 360 it's performance-critical, and it will probably do a better job of it 361 than you would have done). 362 363 Another measure of the function is the number of local variables. They 364 shouldn't exceed 5-10, or you're doing something wrong. Re-think the 365 function, and split it into smaller pieces. A human brain can 366 generally easily keep track of about 7 different things, anything more 367 and it gets confused. You know you're brilliant, but maybe you'd like 368 to understand what you did 2 weeks from now. 369 370 In source files, separate functions with one blank line. If the function is 371 exported, the EXPORT* macro for it should follow immediately after the closing 372 function brace line. E.g.: 373 374 int system_is_up(void) 375 { 376 return system_state == SYSTEM_RUNNING; 377 } 378 EXPORT_SYMBOL(system_is_up); 379 380 In function prototypes, include parameter names with their data types. 381 Although this is not required by the C language, it is preferred in Linux 382 because it is a simple way to add valuable information for the reader. 383 384 385 Chapter 7: Centralized exiting of functions 386 387 Albeit deprecated by some people, the equivalent of the goto statement is 388 used frequently by compilers in form of the unconditional jump instruction. 389 390 The goto statement comes in handy when a function exits from multiple 391 locations and some common work such as cleanup has to be done. 392 393 The rationale is: 394 395 - unconditional statements are easier to understand and follow 396 - nesting is reduced 397 - errors by not updating individual exit points when making 398 modifications are prevented 399 - saves the compiler work to optimize redundant code away ;) 400 401 int fun(int a) 402 { 403 int result = 0; 404 char *buffer = kmalloc(SIZE); 405 406 if (buffer == NULL) 407 return -ENOMEM; 408 409 if (condition1) { 410 while (loop1) { 411 ... 412 } 413 result = 1; 414 goto out; 415 } 416 ... 417 out: 418 kfree(buffer); 419 return result; 420 } 421 422 Chapter 8: Commenting 423 424 Comments are good, but there is also a danger of over-commenting. NEVER 425 try to explain HOW your code works in a comment: it's much better to 426 write the code so that the _working_ is obvious, and it's a waste of 427 time to explain badly written code. 428 429 Generally, you want your comments to tell WHAT your code does, not HOW. 430 Also, try to avoid putting comments inside a function body: if the 431 function is so complex that you need to separately comment parts of it, 432 you should probably go back to chapter 6 for a while. You can make 433 small comments to note or warn about something particularly clever (or 434 ugly), but try to avoid excess. Instead, put the comments at the head 435 of the function, telling people what it does, and possibly WHY it does 436 it. 437 438 When commenting the kernel API functions, please use the kernel-doc format. 439 See the files Documentation/kernel-doc-nano-HOWTO.txt and scripts/kernel-doc 440 for details. 441 442 Linux style for comments is the C89 "/* ... */" style. 443 Don't use C99-style "// ..." comments. 444 445 The preferred style for long (multi-line) comments is: 446 447 /* 448 * This is the preferred style for multi-line 449 * comments in the Linux kernel source code. 450 * Please use it consistently. 451 * 452 * Description: A column of asterisks on the left side, 453 * with beginning and ending almost-blank lines. 454 */ 455 456 For files in net/ and drivers/net/ the preferred style for long (multi-line) 457 comments is a little different. 458 459 /* The preferred comment style for files in net/ and drivers/net 460 * looks like this. 461 * 462 * It is nearly the same as the generally preferred comment style, 463 * but there is no initial almost-blank line. 464 */ 465 466 It's also important to comment data, whether they are basic types or derived 467 types. To this end, use just one data declaration per line (no commas for 468 multiple data declarations). This leaves you room for a small comment on each 469 item, explaining its use. 470 471 472 Chapter 9: You've made a mess of it 473 474 That's OK, we all do. You've probably been told by your long-time Unix 475 user helper that "GNU emacs" automatically formats the C sources for 476 you, and you've noticed that yes, it does do that, but the defaults it 477 uses are less than desirable (in fact, they are worse than random 478 typing - an infinite number of monkeys typing into GNU emacs would never 479 make a good program). 480 481 So, you can either get rid of GNU emacs, or change it to use saner 482 values. To do the latter, you can stick the following in your .emacs file: 483 484 (defun c-lineup-arglist-tabs-only (ignored) 485 "Line up argument lists by tabs, not spaces" 486 (let* ((anchor (c-langelem-pos c-syntactic-element)) 487 (column (c-langelem-2nd-pos c-syntactic-element)) 488 (offset (- (1+ column) anchor)) 489 (steps (floor offset c-basic-offset))) 490 (* (max steps 1) 491 c-basic-offset))) 492 493 (add-hook 'c-mode-common-hook 494 (lambda () 495 ;; Add kernel style 496 (c-add-style 497 "linux-tabs-only" 498 '("linux" (c-offsets-alist 499 (arglist-cont-nonempty 500 c-lineup-gcc-asm-reg 501 c-lineup-arglist-tabs-only)))))) 502 503 (add-hook 'c-mode-hook 504 (lambda () 505 (let ((filename (buffer-file-name))) 506 ;; Enable kernel mode for the appropriate files 507 (when (and filename 508 (string-match (expand-file-name "~/src/linux-trees") 509 filename)) 510 (setq indent-tabs-mode t) 511 (c-set-style "linux-tabs-only"))))) 512 513 This will make emacs go better with the kernel coding style for C 514 files below ~/src/linux-trees. 515 516 But even if you fail in getting emacs to do sane formatting, not 517 everything is lost: use "indent". 518 519 Now, again, GNU indent has the same brain-dead settings that GNU emacs 520 has, which is why you need to give it a few command line options. 521 However, that's not too bad, because even the makers of GNU indent 522 recognize the authority of K&R (the GNU people aren't evil, they are 523 just severely misguided in this matter), so you just give indent the 524 options "-kr -i8" (stands for "K&R, 8 character indents"), or use 525 "scripts/Lindent", which indents in the latest style. 526 527 "indent" has a lot of options, and especially when it comes to comment 528 re-formatting you may want to take a look at the man page. But 529 remember: "indent" is not a fix for bad programming. 530 531 532 Chapter 10: Kconfig configuration files 533 534 For all of the Kconfig* configuration files throughout the source tree, 535 the indentation is somewhat different. Lines under a "config" definition 536 are indented with one tab, while help text is indented an additional two 537 spaces. Example: 538 539 config AUDIT 540 bool "Auditing support" 541 depends on NET 542 help 543 Enable auditing infrastructure that can be used with another 544 kernel subsystem, such as SELinux (which requires this for 545 logging of avc messages output). Does not do system-call 546 auditing without CONFIG_AUDITSYSCALL. 547 548 Features that might still be considered unstable should be defined as 549 dependent on "EXPERIMENTAL": 550 551 config SLUB 552 depends on EXPERIMENTAL && !ARCH_USES_SLAB_PAGE_STRUCT 553 bool "SLUB (Unqueued Allocator)" 554 ... 555 556 while seriously dangerous features (such as write support for certain 557 filesystems) should advertise this prominently in their prompt string: 558 559 config ADFS_FS_RW 560 bool "ADFS write support (DANGEROUS)" 561 depends on ADFS_FS 562 ... 563 564 For full documentation on the configuration files, see the file 565 Documentation/kbuild/kconfig-language.txt. 566 567 568 Chapter 11: Data structures 569 570 Data structures that have visibility outside the single-threaded 571 environment they are created and destroyed in should always have 572 reference counts. In the kernel, garbage collection doesn't exist (and 573 outside the kernel garbage collection is slow and inefficient), which 574 means that you absolutely _have_ to reference count all your uses. 575 576 Reference counting means that you can avoid locking, and allows multiple 577 users to have access to the data structure in parallel - and not having 578 to worry about the structure suddenly going away from under them just 579 because they slept or did something else for a while. 580 581 Note that locking is _not_ a replacement for reference counting. 582 Locking is used to keep data structures coherent, while reference 583 counting is a memory management technique. Usually both are needed, and 584 they are not to be confused with each other. 585 586 Many data structures can indeed have two levels of reference counting, 587 when there are users of different "classes". The subclass count counts 588 the number of subclass users, and decrements the global count just once 589 when the subclass count goes to zero. 590 591 Examples of this kind of "multi-level-reference-counting" can be found in 592 memory management ("struct mm_struct": mm_users and mm_count), and in 593 filesystem code ("struct super_block": s_count and s_active). 594 595 Remember: if another thread can find your data structure, and you don't 596 have a reference count on it, you almost certainly have a bug. 597 598 599 Chapter 12: Macros, Enums and RTL 600 601 Names of macros defining constants and labels in enums are capitalized. 602 603 #define CONSTANT 0x12345 604 605 Enums are preferred when defining several related constants. 606 607 CAPITALIZED macro names are appreciated but macros resembling functions 608 may be named in lower case. 609 610 Generally, inline functions are preferable to macros resembling functions. 611 612 Macros with multiple statements should be enclosed in a do - while block: 613 614 #define macrofun(a, b, c) \ 615 do { \ 616 if (a == 5) \ 617 do_this(b, c); \ 618 } while (0) 619 620 Things to avoid when using macros: 621 622 1) macros that affect control flow: 623 624 #define FOO(x) \ 625 do { \ 626 if (blah(x) < 0) \ 627 return -EBUGGERED; \ 628 } while(0) 629 630 is a _very_ bad idea. It looks like a function call but exits the "calling" 631 function; don't break the internal parsers of those who will read the code. 632 633 2) macros that depend on having a local variable with a magic name: 634 635 #define FOO(val) bar(index, val) 636 637 might look like a good thing, but it's confusing as hell when one reads the 638 code and it's prone to breakage from seemingly innocent changes. 639 640 3) macros with arguments that are used as l-values: FOO(x) = y; will 641 bite you if somebody e.g. turns FOO into an inline function. 642 643 4) forgetting about precedence: macros defining constants using expressions 644 must enclose the expression in parentheses. Beware of similar issues with 645 macros using parameters. 646 647 #define CONSTANT 0x4000 648 #define CONSTEXP (CONSTANT | 3) 649 650 The cpp manual deals with macros exhaustively. The gcc internals manual also 651 covers RTL which is used frequently with assembly language in the kernel. 652 653 654 Chapter 13: Printing kernel messages 655 656 Kernel developers like to be seen as literate. Do mind the spelling 657 of kernel messages to make a good impression. Do not use crippled 658 words like "dont"; use "do not" or "don't" instead. Make the messages 659 concise, clear, and unambiguous. 660 661 Kernel messages do not have to be terminated with a period. 662 663 Printing numbers in parentheses (%d) adds no value and should be avoided. 664 665 There are a number of driver model diagnostic macros in <linux/device.h> 666 which you should use to make sure messages are matched to the right device 667 and driver, and are tagged with the right level: dev_err(), dev_warn(), 668 dev_info(), and so forth. For messages that aren't associated with a 669 particular device, <linux/printk.h> defines pr_debug() and pr_info(). 670 671 Coming up with good debugging messages can be quite a challenge; and once 672 you have them, they can be a huge help for remote troubleshooting. Such 673 messages should be compiled out when the DEBUG symbol is not defined (that 674 is, by default they are not included). When you use dev_dbg() or pr_debug(), 675 that's automatic. Many subsystems have Kconfig options to turn on -DDEBUG. 676 A related convention uses VERBOSE_DEBUG to add dev_vdbg() messages to the 677 ones already enabled by DEBUG. 678 679 680 Chapter 14: Allocating memory 681 682 The kernel provides the following general purpose memory allocators: 683 kmalloc(), kzalloc(), kmalloc_array(), kcalloc(), vmalloc(), and 684 vzalloc(). Please refer to the API documentation for further information 685 about them. 686 687 The preferred form for passing a size of a struct is the following: 688 689 p = kmalloc(sizeof(*p), ...); 690 691 The alternative form where struct name is spelled out hurts readability and 692 introduces an opportunity for a bug when the pointer variable type is changed 693 but the corresponding sizeof that is passed to a memory allocator is not. 694 695 Casting the return value which is a void pointer is redundant. The conversion 696 from void pointer to any other pointer type is guaranteed by the C programming 697 language. 698 699 The preferred form for allocating an array is the following: 700 701 p = kmalloc_array(n, sizeof(...), ...); 702 703 The preferred form for allocating a zeroed array is the following: 704 705 p = kcalloc(n, sizeof(...), ...); 706 707 Both forms check for overflow on the allocation size n * sizeof(...), 708 and return NULL if that occurred. 709 710 711 Chapter 15: The inline disease 712 713 There appears to be a common misperception that gcc has a magic "make me 714 faster" speedup option called "inline". While the use of inlines can be 715 appropriate (for example as a means of replacing macros, see Chapter 12), it 716 very often is not. Abundant use of the inline keyword leads to a much bigger 717 kernel, which in turn slows the system as a whole down, due to a bigger 718 icache footprint for the CPU and simply because there is less memory 719 available for the pagecache. Just think about it; a pagecache miss causes a 720 disk seek, which easily takes 5 milliseconds. There are a LOT of cpu cycles 721 that can go into these 5 milliseconds. 722 723 A reasonable rule of thumb is to not put inline at functions that have more 724 than 3 lines of code in them. An exception to this rule are the cases where 725 a parameter is known to be a compiletime constant, and as a result of this 726 constantness you *know* the compiler will be able to optimize most of your 727 function away at compile time. For a good example of this later case, see 728 the kmalloc() inline function. 729 730 Often people argue that adding inline to functions that are static and used 731 only once is always a win since there is no space tradeoff. While this is 732 technically correct, gcc is capable of inlining these automatically without 733 help, and the maintenance issue of removing the inline when a second user 734 appears outweighs the potential value of the hint that tells gcc to do 735 something it would have done anyway. 736 737 738 Chapter 16: Function return values and names 739 740 Functions can return values of many different kinds, and one of the 741 most common is a value indicating whether the function succeeded or 742 failed. Such a value can be represented as an error-code integer 743 (-Exxx = failure, 0 = success) or a "succeeded" boolean (0 = failure, 744 non-zero = success). 745 746 Mixing up these two sorts of representations is a fertile source of 747 difficult-to-find bugs. If the C language included a strong distinction 748 between integers and booleans then the compiler would find these mistakes 749 for us... but it doesn't. To help prevent such bugs, always follow this 750 convention: 751 752 If the name of a function is an action or an imperative command, 753 the function should return an error-code integer. If the name 754 is a predicate, the function should return a "succeeded" boolean. 755 756 For example, "add work" is a command, and the add_work() function returns 0 757 for success or -EBUSY for failure. In the same way, "PCI device present" is 758 a predicate, and the pci_dev_present() function returns 1 if it succeeds in 759 finding a matching device or 0 if it doesn't. 760 761 All EXPORTed functions must respect this convention, and so should all 762 public functions. Private (static) functions need not, but it is 763 recommended that they do. 764 765 Functions whose return value is the actual result of a computation, rather 766 than an indication of whether the computation succeeded, are not subject to 767 this rule. Generally they indicate failure by returning some out-of-range 768 result. Typical examples would be functions that return pointers; they use 769 NULL or the ERR_PTR mechanism to report failure. 770 771 772 Chapter 17: Don't re-invent the kernel macros 773 774 The header file include/linux/kernel.h contains a number of macros that 775 you should use, rather than explicitly coding some variant of them yourself. 776 For example, if you need to calculate the length of an array, take advantage 777 of the macro 778 779 #define ARRAY_SIZE(x) (sizeof(x) / sizeof((x)[0])) 780 781 Similarly, if you need to calculate the size of some structure member, use 782 783 #define FIELD_SIZEOF(t, f) (sizeof(((t*)0)->f)) 784 785 There are also min() and max() macros that do strict type checking if you 786 need them. Feel free to peruse that header file to see what else is already 787 defined that you shouldn't reproduce in your code. 788 789 790 Chapter 18: Editor modelines and other cruft 791 792 Some editors can interpret configuration information embedded in source files, 793 indicated with special markers. For example, emacs interprets lines marked 794 like this: 795 796 -*- mode: c -*- 797 798 Or like this: 799 800 /* 801 Local Variables: 802 compile-command: "gcc -DMAGIC_DEBUG_FLAG foo.c" 803 End: 804 */ 805 806 Vim interprets markers that look like this: 807 808 /* vim:set sw=8 noet */ 809 810 Do not include any of these in source files. People have their own personal 811 editor configurations, and your source files should not override them. This 812 includes markers for indentation and mode configuration. People may use their 813 own custom mode, or may have some other magic method for making indentation 814 work correctly. 815 816 817 Chapter 19: Inline assembly 818 819 In architecture-specific code, you may need to use inline assembly to interface 820 with CPU or platform functionality. Don't hesitate to do so when necessary. 821 However, don't use inline assembly gratuitously when C can do the job. You can 822 and should poke hardware from C when possible. 823 824 Consider writing simple helper functions that wrap common bits of inline 825 assembly, rather than repeatedly writing them with slight variations. Remember 826 that inline assembly can use C parameters. 827 828 Large, non-trivial assembly functions should go in .S files, with corresponding 829 C prototypes defined in C header files. The C prototypes for assembly 830 functions should use "asmlinkage". 831 832 You may need to mark your asm statement as volatile, to prevent GCC from 833 removing it if GCC doesn't notice any side effects. You don't always need to 834 do so, though, and doing so unnecessarily can limit optimization. 835 836 When writing a single inline assembly statement containing multiple 837 instructions, put each instruction on a separate line in a separate quoted 838 string, and end each string except the last with \n\t to properly indent the 839 next instruction in the assembly output: 840 841 asm ("magic %reg1, #42\n\t" 842 "more_magic %reg2, %reg3" 843 : /* outputs */ : /* inputs */ : /* clobbers */); 844 845 846 847 Appendix I: References 848 849 The C Programming Language, Second Edition 850 by Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie. 851 Prentice Hall, Inc., 1988. 852 ISBN 0-13-110362-8 (paperback), 0-13-110370-9 (hardback). 853 URL: http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/cbook/ 854 855 The Practice of Programming 856 by Brian W. Kernighan and Rob Pike. 857 Addison-Wesley, Inc., 1999. 858 ISBN 0-201-61586-X. 859 URL: http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/tpop/ 860 861 GNU manuals - where in compliance with K&R and this text - for cpp, gcc, 862 gcc internals and indent, all available from http://www.gnu.org/manual/ 863 864 WG14 is the international standardization working group for the programming 865 language C, URL: http://www.open-std.org/JTC1/SC22/WG14/ 866 867 Kernel CodingStyle, by greg@kroah.com at OLS 2002: 868 http://www.kroah.com/linux/talks/ols_2002_kernel_codingstyle_talk/html/

推荐