shared from http://www.samvitjain.com/blog/evaluating-startups/

Choosing a company to work for is an investment. While a venture capitalist might put in a large amount of money and a small amount of their time (i.e. in monthly board meetings) into a portfolio company, as an employee, the primary asset you invest is your time.

The returns you make can take a number of forms - career advancement, personal growth and fulfillment, and financial payoff. Making any decision comes with an opportunity cost - the foregone returns of another choice you could have made.

Finally, unlike a venture capitalist, as an employee, you commit to working at a single place, so you can only make one investment at any given point in time. So while Marc Andreessen might be okay with a 1-in-10 hit rate,1 you have to set the bar a little higher.

All of this is not to paint the decision as a paralyzingly difficult one, but to place it in its proper context - as a prospective employee, you are an investor, and you evaluate companies as much as they evaluate you.

The brand recognition of a company, the capital raised, the prestige of the investors, your friends' opinion - all of these might matter, but perhaps only as secondary signals of a company's future prospects. What, then, should you look for, and how much weight should you put on each factor?

Here's a laundry list of potential criteria that you might consider in evaluating a startup:

- Current traction (i.e. users, revenue)

- Growth rate (i.e. users, revenue)

- Number of employees

- Strength of founders

- Strength of early employees

- Investor pedigree (i.e. reputation, past record)

- Rounds of funding raised

- Location

- Personal fit

In the remainder of the post, I'll address each of these in turn, and provide a "star rating" to indicate how strongly you should consider each factor when making your decision.

I assume that you are interested in some combination of the following: personal growth, career growth, and financial upside. A convenient truth is that these three goals tend to be tightly correlated, and joining an early-stage, fast-growing startup with strong founders and talented employees is likely to satisfy all three.

This post is about how to identify such companies.

Current traction

One fact that makes evaluating startups as a prospective employee particularly difficult is that most key metrics are not public information. Statistics such as the number of monthly or daily active users (MAUs/DAUs), annual revenue, and months of the runway are often not even known to current employees, let alone available on the internet.

Moreover, the founders and upper management are unlikely to share this information in the interview process, but if you do get the chance to speak with them, it is definitely worth a shot to ask.

Even if these numbers are known, they may not actually be the strongest signals. Revenue, for example, is often an irrelevant measure for early-stage, consumer-facing companies (e.g. Facebook in 2008), while the number of clients may be too coarse a metric for early-stage, enterprise tech companies (for many years, Palantir only had one customer: the US government).

You also have to be careful about companies cherry picking statistics that paint them in a favorable light. A mobile app company may choose to reveal total downloads, but not monthly active users, or their shockingly high churn (i.e. uninstall) rate.

A famous example where these metrics sharply conflicted is Draw Something, a social drawing app, which, along with its parent company OMGPop, was acquired by Zynga in March 2012 for $180 million. Within two months of the purchase, daily active users had fallen by a third, from a peak of 15 million on the day of the sale to 10 million by early May. Draw Something relied on aggressive growth hacking, via close integration with Facebook, and sacrificed the opportunity to build a sustainable product for rapid growth.

The result? One of the greatest "pops" of the social-local-mobile app era.

Growth rate

This one is tricky. Growth figures, especially when measured over only two data points (metrics today vs. metrics last year), are often hard to evaluate, unless absolute numbers are known as well. A representative from Facebook could have reported a 2150% growth in revenue in 2005. While Facebook was indeed growing incredibly fast at that time, that particular statistic is meaningless, as revenue was nearly zero in 2004.

This is not just a straw man argument. Various startups that I've interviewed with have claimed that they "doubled in revenue since last year," or even that they've been "doubling in revenue every year" when the company has only been in existence for 3 years, without providing a clear estimate of current revenue.

You should ask yourself why a company is choosing to share growth numbers, but not any absolute figures. It's likely because growth statistics are a lot more flattering to the company. But you should know: being a derivative of the yearly revenue (or total users) graph, growth figures will almost always contain less information.

Of course, don't be pedantic. If a founder mentions that their service has over a million users, and is sporting 200% year-over-year growth, but won't give exact numbers, you probably have enough information to judge that the business is growing rapidly.

Cynicism aside, joining a company that is growing at a breakneck pace is one of the smartest career decisions you can make early on. Such a startup will offer many opportunities to take charge and grow into leadership roles and will be filled with intelligent and ambitious young people - colleagues who may become your business partners and co-founders one day. Finally, as many have said, getting a win on your record early in your career is incredibly valuable, and as I discuss in the last section, early hyper growth is one of the strongest signals that a company will do very, very well in the future. Of course, true hyper growth is rare, and identifying such companies when they're relatively small and unheard of is challenging. But your alternative is the even harder problem of trying to turn around a slow-growing company as employee #50.

On the flip side, joining a startup that "fails" a year or two after you join is not as bad as you may think. Assuming the startup had clear potential and a high hiring bar, no one will hold it against you that the company didn't do as well as hoped. This attitude may not hold outside the San Francisco Bay Area, or the United States, but what is most threatened by spending time at a company that flounders is not your CV, but just that: your time. Staying at a company with no clear growth prospects for five years translates to five lost years you could have spent growing and learning. Note that this idea that a failed startup does not equal a black mark on your career holds for both the founders and the employees. That said, you are probably less likely to regret time spent working on a problem you deeply care about as a founder than as employee #50.

Number of employees

Cisco Systems has 70,000 employees today, and its stock price has hovered between $15 and $30 for the past 16 years. When WhatsApp was acquired by Facebook for $19 billion in February 2014, it had 55 employees.

Evidently, headcount alone says little about a company's quality. But the number of employees, combined with the most recent valuation of the company, can give you some idea for how much money you stand to make if you join.

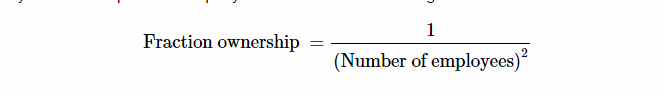

Here's the heuristic. Stocks generally vest over four years, and if you stay the four years, your ownership of the company will amount to the following:

This can now be used to calculate your potential upside. If you join a 100-person startup valued at $500 million and work there for four years, you'll be granted shares constituting

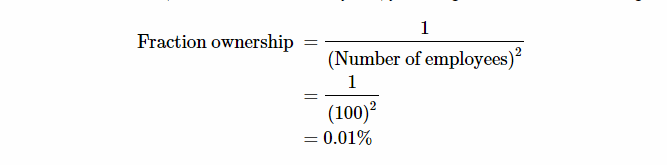

of the company. If the company is then acquired for $5 billion, you will stand to make:

(Here I'm not considering the strike price of your stock options, i.e. how much you'll need to pay the company to exercise them.)

What evidence do I have that this is true? This equation correctly predicts (to within about 40%) the value of equity I was offered at the one company to which I applied to for a full-time job on graduation. (Its output was a bit conservative.) Its predictions also resemble those of this more precise calculator, which takes slightly different inputs.

Finally, it has the following very nice property:

Take this formula for what it is: a heuristic for your ownership stake in a startup. In particular, percent ownership alone says nothing about your potential upside. To estimate upside, you need to consider a range of possible trajectories that the company could take after you join. If you join a company that goes under or is acquired for peanuts, it won't matter if you own 1% of it or 0.01% of it. 1% of 0 is still 0.

Strength of founders

Full disclosure: this is the only criteria in this list that I gave the full five stars to. And for good reason too. As venture capitalists have said for time immemorial, it is the founding team, of all aspects of a company, that has the strongest bearing on its eventual fate.

As a quick exercise, consider these short, 2-sentence bios of the founders of the five most valuable tech companies in the world today:

-

Facebook - Mark Zuckerberg began programming in middle school, going on to build an intelligent music player, Synapse, that AOL and Microsoft offered up to $1 million to buy, while still in high school.2 At Harvard, Zuckerberg established a reputation for building popular social tools for his peers, including Facemash, the traffic from which crashed Harvard's servers and the security breaches involved in which nearly got him expelled.

-

Amazon - Jeff Bezos entered Princeton intending to study physics, with the goal of becoming a theoretical physicist, but exited an electrical engineering and computer science major, graduating near the top of his class, and as president of the Princeton chapter of Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. During his 8 year career on Wall Street, Bezos rose to become the then two-year-old hedge fund D. E. Shaw's youngest vice president.

-

Microsoft - Bill Gates began programming in 8th grade on a computer donated to his high school, which he used for everything from writing simple games, to exploiting bugs in the time sharing system - an exploit which temporarily cost him his computer privileges, to developing a payroll program for the donating company. While at Harvard, he solved a minor, open combinatorics problem, and as a proof-of-concept aimed at hobbyists, implemented an interpreter for the BASIC language for the Altair 8800 mini-computer.

-

Alphabet - A computer science and mathematics major at the University of Maryland, Sergey Brin began his Ph.D. studies in computer science at Stanford in 1994; a computer engineering major at the University of Michigan, and an inventive engineering student, Larry Page began his Ph.D. at Stanford in 1995. Among other topics, Page considered doing research on telepresence and autonomous cars, but along with Brin, decided to focus on exploring the graph structure of the rapidly growing World Wide Web.

-

Apple - In high school, Steve Jobs demonstrated diverse interests, from Shakespeare and Plato to creative writing, to electronics, enrolling in a freshman English class at Stanford during his senior year, and then dropping out of Reed College after 6 months. Jobs later moved to India, where he lived in an ashram for seven months; later still, he took up a contract project for Atari, enlisting the help of Steve Wozniak to construct a highly-optimized circuit board for an arcade game, a deal that earned him $5,000.

What do you notice about these six founders?

Three dropped out of college, and one pair dropped out of grad school. Five out of six were highly technical. None were serial entrepreneurs. Five out of six did not have any professional experience.

Yes, unfortunately, they were also all white males, born in most cases into privilege and into supportive, two-parent households.3

But what personal qualities come up repeatedly in these descriptions? Intensity, ambition, clear passions - many times established at a young age, and often, a disregard for rules.

In an interview with Vogue, Jennifer Lawrence, the highest paid actress in the world today, once said, with some hesitation, that she "always knew that [she] was going to be famous." To the list of characteristics, I would then also add, a certain belief in their own predestination.4

Notice also that, today, Jeff Bezos is the owner of Blue Origin, one of the two leading space exploration companies, and Alphabet is the industry leader in the self-driving car space. Evidently, Bezos' early interest in space colonization and Page's attraction to autonomous cars weren't fake passions, but deeply-seated ambitions - visions for how the future should look like that they acted on as soon as they got the chance.

While their biographies may sound impressive, none of these accomplishments are particularly uncommon, and I challenge you to hold the founders of your potential employer to the same high standard. Can you write a 2-sentence bio of each of the founders that reflects a similar caliber of achievement?

In your description, try to focus on concrete accomplishments, as opposed to proper nouns. Instead of writing, "Sarah graduated from Harvard as a public policy major, and worked at Goldman Sachs for two years," write: "Sarah graduated from Harvard, where she worked to develop novel financial instruments allowing emigrants from oppressive regimes to remotely liquidate their assets, even testing her research through a live study based in Syria. While at Goldman Sachs, she helped to expand the bank's portfolio of consumer fin-tech companies, and personally oversaw late-stage financing for three Bitcoin and blockchain-related startups."

This second Sarah would make a great founding CEO or COO for a blockchain-based, smart property startup. Sarah is a self-starter, with a history of building new things and sticking with them until they see adoption. She has a demonstrated interest in shaping the future through invention, as opposed to simply an interest in advancing herself. She has also successfully faced competition - it is not easy to get accepted to Harvard, and it is not easy to get a job at Goldman Sachs.

So Sarah may have what it takes to beat the odds that the company she'll start will get killed - by its burn rate, by disputes between its founders, by its failure to find product-market fit, by its competitors, by shifts in the market.5

What kinds of past experience are signs of a great founder?

-

Pivotal role in a very successful company - This is rare, but a very strong sign when true. Two great examples are Dustin Moskovitz, a co-founder of Facebook, and Adam D'Angelo, Facebook's first CTO, who each went on to start extremely well-run companies, Asana and Quora, respectively. Dustin and Adam combine front-line experience in a rocket ship, with a genuine thirst to build companies of their own - both were in some sense sidelined at circa 2008 Facebook, which only had room for one real leader at its helm. Asana emerged as an internal project at Facebook, and Adam left two years of equity at Facebook on the table to found Quora, strong circumstantial evidence that the problems they chose to tackle were relevant and valuable.

-

The fourth-time founder, aka the serial entrepreneur - I have more mixed feelings about this one. Being a serial entrepreneur is considered a great resume item in some circles, and there are of course a few example of wildly successful born-again founders - notably, Elon Musk, and even Steve Jobs, who founded NeXT Computer between 1980s Apple and iPod/iPhone-era Apple. Entrepreneurship is a difficult journey, and the greatest founders tend to treat their companies as their life's work. A long history of eight-figure acquisitions doesn't speak very well to a founder's dedication, and their ability to navigate difficult times to take a company to greatness. Be especially wary if there's a trail of people who've worked with the founder in the past, and have felt screwed over.

-

Domain expertise - This is valuable, but probably not strictly necessary. This Y Combinator-backed waste management company recently raised a $12 million Series A round and includes a founder whose family has been in the waste recycling business for four generations. That sounds splendid to me and is an attribute that investors often assign big plus points to. But being an outsider can sometimes constitute a great advantage as well. Elon Musk had no formal experience in rockets or electric cars when he started SpaceX and Tesla, two areas that seem to have extremely high barriers to entry. Moral: we probably overestimate how hard it is for smart people to immerse themselves in new, hard problems they care about.

Strength of early employees

I have a controversial heuristic for judging the quality of the early employees at a company. I get on LinkedIn, and jump from profile to profile, looking at the schools they've attended and the companies they've worked for. I consider it a pretty big red flag if most attended seemingly weak schools and worked for companies I've never heard of. This sounds at best naive and at worst prejudiced, so let me defend myself.

In my experience, the best startups have at least some junior employees who attended schools like Stanford, MIT, and Harvard.1 This was true of early Google and early Facebook and is true today of companies like Dropbox, Stripe, Airbnb, and Quora. If a startup doesn't have any students from such schools, it says to me one of two things:

-

The founders and their first hires do not have a network that extends to new grads from these schools.

-

The startup cannot convince students at these schools to come work for them.

The first is more benign than the second. Great founders come from lots of different places, and some may just not be connected to students at top schools. After the startup becomes a certain size, however, and reaches a certain level of notoriety, this excuse becomes a little weaker.

The second reflects a little less favorably but is understandable. Recruiting smart people is really, really hard. I know this because I spent several months in early 2015 searching for Employee #1 for my nascent, pre-seed venture, LinkMeUp. I set up shop at a startup career fair at Princeton, posted in college and Hackathon Facebook groups, and even upgraded to LinkedIn Premium, where I sent many an unsolicited message to undergrads in my extended network. I interviewed several candidates for an Android engineering role, some of whom I turned down and several others more who turned me down.

Moral of the story: it's hard to convince people to turn down offers from Google, Facebook, Uber, Airbnb, etc. to come work for your shitty company that might fail. But that is exactly the task of a great founding team. They must be accomplished and inspiring enough that smart people want to work for them,2 and clear enough in their articulation of the company's vision to convince smart people that they have a chance at success.

The one thing that distinguishes students at top schools is that they tend to have the most options for what to do in the future, and often the highest opportunity cost for picking any one thing. So if you can convince Harvard grads to join your company, you are either really good at creating hype, or are genuinely offering them an amazing opportunity.

Note that I'm definitely not suggesting that great early employees come only from top schools, or that all (or even most) students at top schools would make great early employees. Both of those statements are patently false. What I am saying is this: being able to recruit from top schools, or from top companies (e.g. ex-Google or ex-Facebook employees), is a decent signal that a company prioritizes hiring very strong people, and is successful at it.

Why do I use credentials like past school and company affiliation to judge that? Mostly for efficiency reasons. Looking up each employee's open source contribution history seems like overkill, and incidentally, would only work for technical recruits. That level of due diligence is completely warranted for the founders of a company (i.e. picking a startup just because the founders went to Stanford is a terrible idea), but may not be necessary for getting a sense for the backgrounds of the early employees.

Of course, please take my advice with a grain of salt. There are people with more experience than me who would disagree with me on this point.

You might also ask: why does hiring strong early employees matter so much anyway? It matters because it is the early employees who will serve as your mentors, and in many cases, become the company's leaders. Besides the founders, the early hires will be the party with the biggest influence on the company's destiny. Relaxing hiring standards is tempting, but the consequences are subtle and self-perpetuating. Rowdy and misogynistic early employees, for example, will very likely build a company that is rowdy and misogynistic.

Investor pedigree

If I was looking for a job, and I saw that a company was backed by Sequoia Capital, I would be tempted to go work for them - even if their founders were five years old.

Here's a list of companies whose Series A or B rounds (or both) were led by Sequoia: Apple, Google, Yahoo!, Stripe, Dropbox, YouTube, Instagram, Airbnb, and WhatsApp.

Of Sequoia's over 1000 investments since 1972, 209 companies have been acquired and 69 have IPOed. Their mission statement:

The creative spirits. The underdogs. The resolute. The determined. The outsiders. The defiant. The independent thinkers. The fighters and the true believers.

These are the founders with whom we partner. They’re extremely rare. And we’re ecstatic when we find them...

We’re serious about our work, and carefully choose the words to describe it. Terms like “deal” or “exit” are forbidden. And while we’re sometimes called investors, that is not our frame of mind. We consider ourselves partners for the long term.

We help the daring build legendary companies.

If that doesn't capture the ethos of Silicon Valley, I don't know what does.

This is a criterion that my intuition would award 4.5 stars to, but that even investors themselves would warn against overvaluing. So I compromised and gave it 4 stars.

Silicon Valley has a hierarchy in its investors. The top-tier is generally agreed to consist of Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers (KPCB), Greylock, Benchmark, Accel, and Andreessen Horowitz.3 Other well-known venture firms include General Catalyst, New Enterprise Associates (NEA), and Lightspeed. These are the venture capital firms that, in general, attract the best founders, win the best deals, and show the highest returns.

Even the best firms, however, often miss great deals, so the failure to raise funding from one of these groups does not necessarily imply weakness. This is particularly true of companies founded outside of the U.S., and of very promising founders who may have weaker connections to Silicon Valley's old guard (though these firms have gotten pretty good at identifying unknown upstarts).

On the flip side, not all companies funded by top-tier venture firms are excellent places to work. It is the nature of their business that venture capital firms will invest in a large number of companies that will fail. More than that, promising companies can sometimes degenerate if their growth is achieved at the cost of their culture or values. Even if Sequoia is behind them, such startups should be avoided like the plague.

Rounds of funding raised

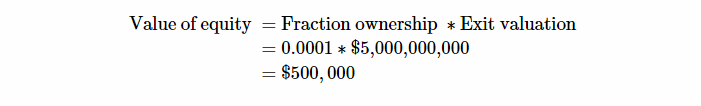

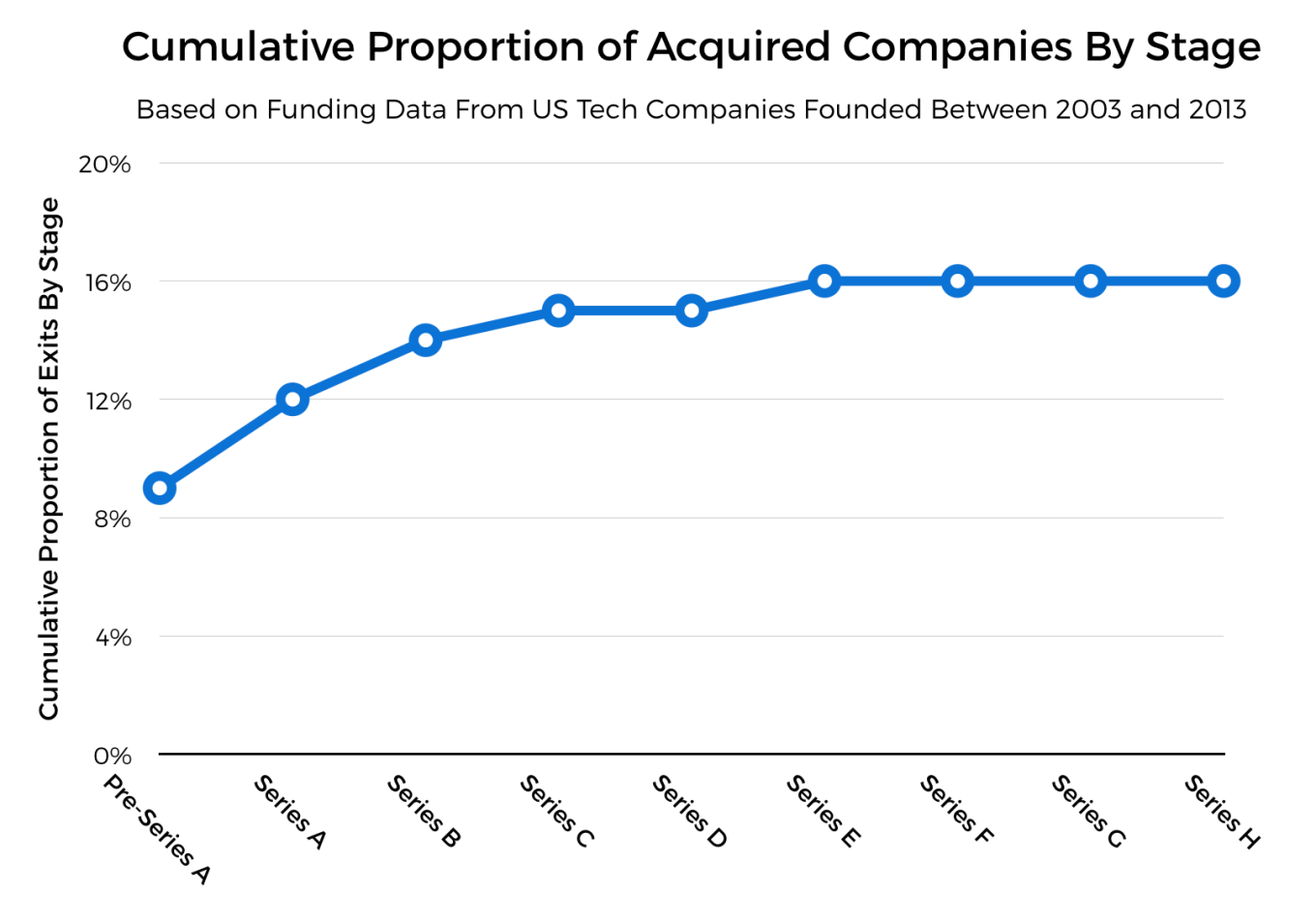

The funding statistics in this section are based on a 2017 article by TechCrunch that looked at 15,600 U.S.-based tech companies founded between 2003 and 2013.

As a sanity check, I also compared these numbers with those from a similar Business Insider article from 2016. The BI funding statistics are slightly more conservative.

The number of rounds of funding raised by a company is a decent indicator of how much risk the startup has neutralized, or in other words, how likely the company is to succeed at some level.

This doesn't mean that it is always better to join a company that has raised a Series C round over a company that has only raised a B round because there is a tradeoff. The Series C company will be offering a smaller equity share, possibility significantly so, and thus less potential upside. In addition, some types of funding rounds can actually be indicative of problems in the company - notably, down rounds and debt financing.4

A company that has raised no external funding should be considered "extremely high risk", and not being offered founder-level equity at such a company should be met with extreme skepticism. (Especially because you are likely to be working for little to no pay for a while.)

A company that has raised a seed round is officially a funded startup, but is still "high risk", as only about 40% of seed-funded companies go on to raise Series A rounds, and only about 9% get acquired. Seeds rounds are usually raised from individual investors (i.e. angels) or specialized funds, such as Y Combinator, Founders Fund, and SV Angel, and generally, involve on the order of $0.5-1 million in the capital.

Figure 1: Startup funding drop-off curve, not including acquisitions (Source: TechCrunch)

Figure 1: Startup funding drop-off curve, not including acquisitions (Source: TechCrunch) Figure 2: Startup cumulative acquisition graph (Source: TechCrunch)

Figure 2: Startup cumulative acquisition graph (Source: TechCrunch)

A company that has raised a Series A round should be considered "moderate risk". Of companies that raise an A round, about 62.5% go on to raise a Series B round, and 7.5% get acquired, which implies that the other 30% likely die. In terms of career growth and financial upside, this is probably the best time to join a startup that scores highly on all of the other criteria. Series A companies still have high growth potential, and yet have been formally validated by a group whose full-time job it is to evaluate early-stage start-ups. As a prospective employee, you now have an additional data point: the reputation of the venture capital firm that led the Series A round.

Series B round companies should be considered "low-risk".5 For one, companies that have raised a Series B are almost always generating revenue. Series B round investors look for evidence of healthy growth in users or customers since the A round, meaning that Series B companies have been validated not only on company fundamentals (team, product, market) but also on more complex signals, such as product-market fit. The median Series B round size, as of July 2015, was $18.4 million, implying that the median Series B company is valued on the order of $100 million.

When evaluating a startup on its funding history, an important factor to consider is when the last round of funding was raised. A Series B company founded in 2005 that hasn't raised any venture capital since 2008, and has not IPOed, is either 1) reliant on its own revenue, and likely slow growing (i.e. not really a startup), or 2) approaching death.6

A point to note: companies that have raised a Series B round or beyond should be offering a base salary that is competitive with that offered by larger, public companies. For new college grads, the average base salary offered by top-tier tech companies based in San Francisco was $110,000, as of mid-2017. Take this figure with a grain of salt (and, of course, don't neglect cost of living adjustments), but if you're being offered much less, you're either at a company with an unusual compensation structure (and should be offered a significantly above-average equity grant), or are not being made a fair offer.7

Note also that raising an advanced stage of funding (e.g. a Series D or E round) doesn't signify with certainty that the company is immune from death. Silicon Valley history is replete with examples of startups that were valued at or over $1 billion and were later acquired for much less than that (e.g. Gilt Groupe, One Kings Lane, LivingSocial), and companies that raised a lot of capital, and then floundered. So I equate rounds of funding with neutralized risk simply as a rough heuristic for estimating the risk-reward tradeoff involved in joining a company.

I would highly recommend asking a founder or executive about the company's current runway during the interview process. This is an estimate for how long the company could stay afloat, given the cash in its bank and its current rate of spending (i.e. burn rate), were it not to raise any more capital. Asking this question definitely does not constitute a faux pax, and an evasive answer should because for alarm.

Location

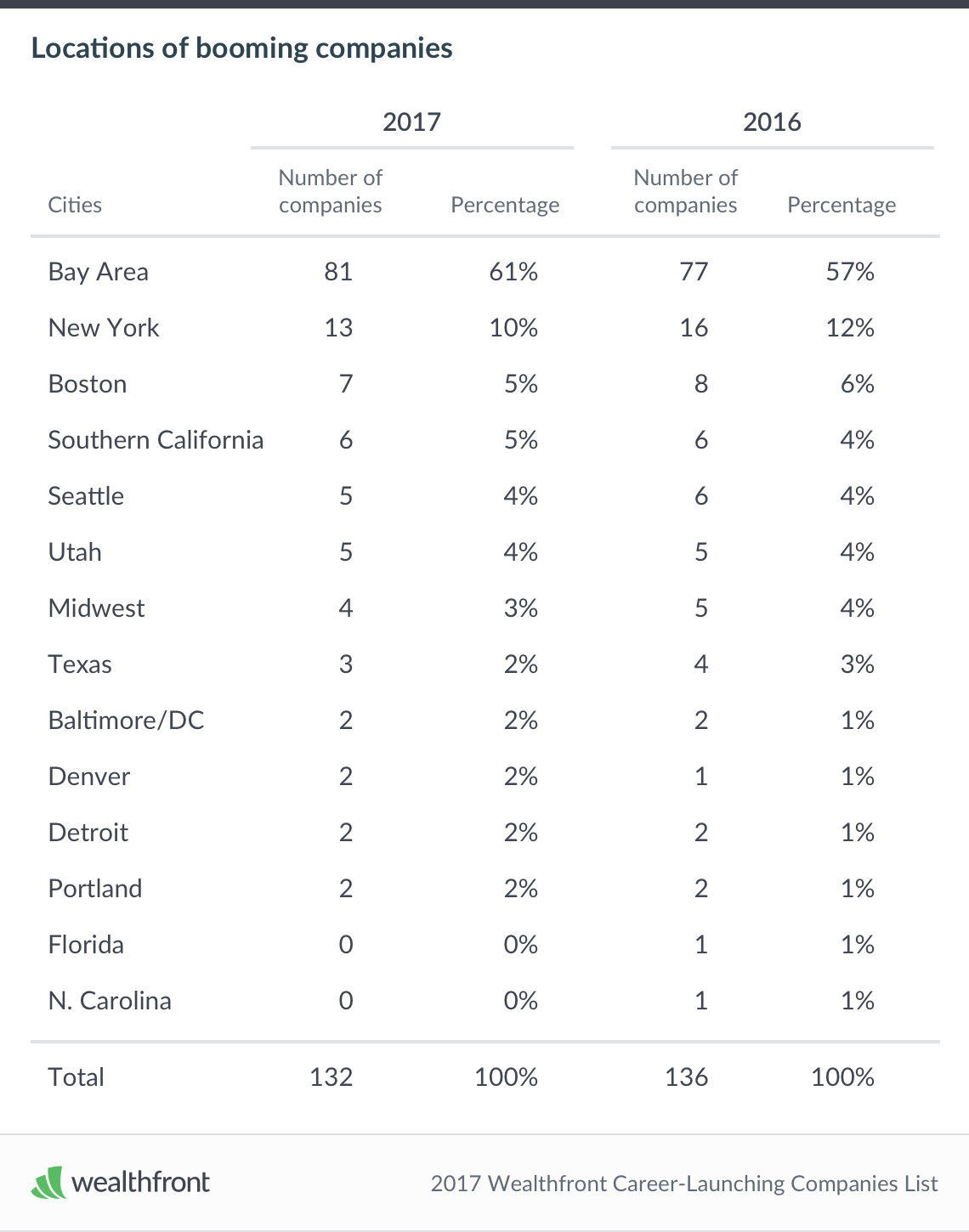

Every year, Wealthfront identifies a set of "career-launching" tech companies for aspiring young professionals by surveying the partners of 14 top venture capital firms. The qualifications for making the list are: 1) a revenue run rate between $20-300 million, and 2) a growth trajectory of over 50% over the next three to four years.

Wealthfront's 2017 posting identifies 132 such companies. Of these, about 61% are located in the San Francisco Bay Area, followed by 10% in New York, 5% in Boston, another 5% in Southern California, and 4% in Seattle. Of the Bay Area companies, about 58% are located in San Francisco itself.

I've included the full table below for reference:

Figure 3: List of Wealthfront's "career-launching" companies, 2017 vs. 2016, by location (Source: Wealthfront Blog)

Figure 3: List of Wealthfront's "career-launching" companies, 2017 vs. 2016, by location (Source: Wealthfront Blog)

Treat location as a fairly grainy, but binary signal of a company's prospects. A company based out of San Francisco, Palo Alto, Menlo Park, or Mountain View is obviously not guaranteed to be successful, but a company not headquartered in the Bay Area or New York (and maybe Boston, Seattle, or LA) is going to be fighting an uphill battle finding investors, attracting and retaining strong employees, and connecting with its early adopters.

Personal fit

I want to play devil's advocate and argue that what a company builds may not actually be that indicative of whether the company would be a good fit for you. Let's say you're interested in machine learning, but you think enterprise tech is super boring.

You could find a job at an MLaaS company8 which builds tools to help genomics researchers more efficiently construct data pipelines, and visualize their results. You thought you'd never enter a world in which companies use aggressive sales tactics to upsell overpriced software to other companies, but you come to realize that writing tools for a small number of clients who place extreme value in the products you build for them is actually quite fulfilling.

You could also find a job at a consumer-facing company that uses machine learning to personalize the content it serves users, and to customize the ad copy it shows them based on the cookie-infested websites they visit. You realize that linear regressions still do pretty well on these kinds of tasks, and though you were initially very excited about contributing to a service that your friends use, it is not actually super riveting in the day-to-day to work there.

The point here is that you should be open-minded about the kinds of problems you could be interested in, and the kinds of work you'd like to do. Don't judge companies solely on their one-sentence mission statements. Instead, take the time to understand what the startup really does, why the problem they're solving is an important one, and what the immediate and future market for their work is.

An example of a startup with a boring-sounding mission statement that does very impactful work (and, incidentally, scores highly on all of the other criteria) is Samsara. Here's a description from their About page:

At Samsara, we believe that by making it easy to deploy sensors and analyze their data, customers of all types will be able to use them by the thousands, and in places they've never been used before.

Started by the two MIT Ph.D. dropouts who co-founded Meraki, an enterprise Wi-Fi networking startup acquired by Cisco for $1.2 billion, and staffed by an exceptional team, Samsara is building tools to enable the real-time tracking and monitoring of fleets and industrial sites via wireless sensors. Samsara is a textbook example of a team with deep domain expertise tackling an immense, emerging market. Even if you don't give a hoot about sensors, their work - which touches on a number of areas, including data science, real-time systems, and machine learning - could be of great interest.

How much does the nature of the work that you do - full-stack, backend, cloud platform, data science - matter, anyway? Your interests matter, and developing an area of competitive advantage as an employee can matter. In startups, however, initial job title and responsibilities are generally dwarfed in importance by the pace of the company's growth. A small, fast growing company will require you to wear many hats, regardless of what your job description says, and assuming it is well managed, will reward exceptional performance commensurately.

On a related note, in this talk, Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder of Facebook and co-founder of Asana, makes the very relevant point that intelligent young people often overvalue working on the most challenging problems. I thought this was such a good point, actually, that I reproduced his exact words here:

A lot of graduating students think I just want to work on the hardest problems. If you are one of these people, I predict that you're going to change your perspective over time. I think that's kind of like a student mentality, of challenging yourself, and proving that you're capable of it. But as you get older, other things start to become important, like personal fulfillment, what are you going to be proud of, what are you going to want to tell your kids about, or your grandkids about, one day.

How will the work that you do add value to the world? As Moskovitz says, this is not a given for every startup. Life is too short to work for a company that does not do work that matters to you, and that matters period.

Closing thoughts

While I've addressed the basic criteria for evaluating start-ups, some of the most important markers of a company's destiny cannot be captured in numbers.

-

How much do users love the product? Do they tell their friends about it?

-

What kind of a product is the company building? The most audacious researchers and entrepreneurs pursue two kinds of problems:

-

0 to 1 systems. These are products that are the first of their kind - not derivatives concocted from existing ideas (e.g. Uber vs. "Uber for pet sitting").

-

10x systems. These are products that are at least an order of magnitude better than whatever is used instead today (e.g. Google search vs. Yahoo/Alta Vista).

-

The great paradox of entrepreneurship is that it is often easier to build a company to solve a hard problem than an easy one. Space exploration, driverless cars, curing infectious disease - these are the ideas that excite and attract smart people, and that inspire loyalty in trying times.

That said, do not discount products that seem like toys as trivialities. Facebook was once just a tool for Harvard students to stalk each other, and Snapchat was something worse. Today, Facebook connects two billion people around the world, and Snapchat enables a hundred million to communicate more authentically.

This is where the first criterion becomes useful. Early Facebook users spent hours clicking from profile to profile (okay, maybe some people still do this), so engrossing was the data that Facebook had made available on their friends. Just over a year after launch, Snapchat users were sending each other about 20 million snaps per day.

Through the dot com bust and the rise of mobile phones, three survivors emerged from the Internet era: Google, Facebook, and Amazon. Google indexes the world's information, Facebook indexes the world's people, and Amazon indexes the world's products. Though on decidedly shakier grounds, the mobile era has spawned its own behemoths. The three enabling forces here are messaging (i.e. low-latency, mobile web-based message exchange), the camera (i.e. the dual-facing, integrated recording device), and location (i.e. high-precision global GPS), and their flag-bearers WhatsApp, Snap, and Uber.

In a similar way, each technological wave spawns companies of all kinds, but the most persisting are the ones that capture the most fundamental, the lowest-hanging fruit. This is always easier to spot in retrospect, of course. The best companies tend to execute on ruthlessly narrow domains to start out, and then expand rapidly to realize a wider potential. Early Google ranked textual pages. Early Facebook connected college students. Early Amazon sold books. Today, Google is using AI to drive cars, Facebook is beaming down Wi-Fi to the world's disconnected, and Amazon is launching drones to automate delivery. Their operations span continents, and each wields power rivaling that of the Roman Empire at its height.

Though each of the three had humble origins, I suspect that even in their early days you would have found markers of greatness. The best consumer companies are like child prodigies - they grow faster than you would think possible, surpassing milestones that other, more mature companies, run by professional CEOs and seasoned C-suites, struggled to reach, at breakneck speed. Of course, like child prodigies, some flame out early (e.g. Yik Yak), while others fail to mature into healthy, cash-flow positive adults (e.g. Twitter). But every decade, two or three chart their way to adulthood fame.

I'm not suggesting that a startup is only worth joining if it resembles Google circa 2000 or Facebook circa 2006, but studying the characteristics of the really successful companies does teach you what to look for. Granted, not every startup has a glorified origin story. Companies such as Airbnb, SpaceX, and Tesla weathered many near-death experiences in their early days. In more cases than not, the cost of greatness is great struggle.

So while you can't compare every company to Instagram, which crossed 100,000 users less than a week after its launch in October 2010, you can learn to spot the markers that signal that a company is promising, and on a trajectory that could take you places. I hope this piece serves as a useful guide at least for the common cases, if not for spotting the next Apple Computer in its infancy.