Introduction

A lot of applications use digital images, and with this there is usually a need to process the images used. If you are building your application with Python and need to add image processing features to it, there are various libraries you could use. Some popular ones are OpenCV, scikit-image, Python Imaging Library and Pillow.

We won't debate on which library is the best here, they all have their merits. This article will focus on Pillow, a library that is powerful, provides a wide array of image processing features, and is simple to use.

Pillow is a fork of the Python Imaging Library (PIL). PIL is a library that offers several standard procedures for manipulating images. It's a powerful library, but hasn't been updated since 2011 and doesn't support Python 3. Pillow builds on this, adding more features and support for Python 3. It supports a range of image file formats such as PNG, JPEG, PPM, GIF, TIFF and BMP. We'll see how to perform various operations on images such as cropping, resizing, adding text to images, rotating, greyscaling, e.t.c using this library.

Installation and Project Setup

Before installing Pillow, there are some prerequisites that must be satisfied. These vary for different operating systems. We won't list the different options here, you can find the prerequisites for your particular OS in this installation guide.

After installing the prerequisite libraries, you can install Pillow with `pip:

$ pip install Pillow

To follow along, you can download the images (coutesy of Unsplash) that we'll use in the article. You can also use your own images.

All examples will assume the required images are in the same directory as the python script file being run.

The Image Object

A crucial class in the Python Imaging Library is the Image class. It is defined in the Image module and provides a PIL image on which manipulation operations can be carried out. An instance of this class can be created in several ways: by loading images from a file, creating images from scratch or as a result of processing other images. We'll see all these in use.

To load an image from a file, we use the open() function in the Image module passing it the path to the image.

from PIL import Image

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

If successful, the above returns an Image object. If there was a problem opening the file, an IOError exception will be raised.

After obtaining an Image object, you can now use the methods and attributes defined by the class to process and manipulate it. Let's start by displaying the image. You can do this by calling the show() method on it. This displays the image on an external viewer (usually xv on Unix, and the Paint program on Windows).

image.show()

You can get some details about the image using the object's attributes.

# The file format of the source file.

print(image.format) # Output: JPEG

# The pixel format used by the image. Typical values are “1”, “L”, “RGB”, or “CMYK.”

print(image.mode) # Output: RGB

# Image size, in pixels. The size is given as a 2-tuple (width, height).

print(image.size) # Output: (1200, 776)

# Colour palette table, if any.

print(image.palette) # Output: None

For more on what you can do with the Image class, check out the documentation.

Changing Image Type

When you are done processing an image, you can save it to file with the save()method, passing in the name that will be used to label the image file. When saving an image, you can specify a different extension from its original and the saved image will be converted to the specified format.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

image.save('new_image.png')

The above creates an Image object loaded with the unsplash_01.jpg image and saves it to a new file new_image.png. Pillow sees the file extension has been specified as PNG and so it converts it to PNG before saving it to file. You can provide a second argument to save() to explicitly specify a file format. This image.save('new_image.png', 'PNG') will do the same thing as the previous save(). Usually it's unnecessary to supply this second argument as Pillow will determine the file storage format to use from the filename extension, but if you're using non-standard extensions, then you should always specify the format this way.

Resizing Images

To resize an image, you call the resize() method on it, passing in a two-integer tuple argument representing the width and height of the resized image. The function doesn't modify the used image, it instead returns another Image with the new dimensions.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

new_image = image.resize((400, 400))

new_image.save('image_400.jpg')

print(image.size) # Output: (1200, 776)

print(new_image.size) # Output: (400, 400)

The resize() method returns an image whose width and height exactly match the passed in value. This could be what you want, but at times you might find that the images returned by this function aren't ideal. This is mostly because the function doesn't account for the image's Aspect Ratio, so you might end up with an image that either looks stretched or squished.

You can see this in the newly created image from the above code: image_400.jpg. It looks a bit squished horizontally.

If you want to resize images and keep their aspect ratios, then you should instead use the thumbnail() function to resize them. This also takes a two-integer tuple argument representing the maximum width and maximum height of the thumbnail.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

image.thumbnail((400, 400))

image.save('image_thumbnail.jpg')

print(image.size) # Output: (400, 258)

The above will result in an image sized 400x258, having kept the aspect ratio of the original image. As you can see below, this results in a better looking image.

Another significant difference between the resize() and thumbnail()functions is that the resize() function 'blows out' an image if given parameters that are larger than the original image, while the thumbnail() function doesn't. For example, given an image of size 400x200, a call to resize((1200, 600)) will create a larger sized image 1200x600, thus the image will have lost some definition and is likely to be blurry compared to the original. On the other hand, a call to thumbnail((1200, 600)) using the original image, will result in an image that keeps its size 400x200 since both the width and height are less than the specified maximum width and height.

Cropping

When an image is cropped, a rectangular region inside the image is selected and retained while everything else outside the region is removed. With the Pillow library, you can crop an image with the crop() method of the Image class. The method takes a box tuple that defines the position and size of cropped region and returns an Image object representing the cropped image. The coordinates for the box are (left, upper, right, lower). The cropped section includes the left column and the upper row of pixels and goes up to (but doesn't include) the right column and bottom row of pixels. This is better explained with an example.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

box = (150, 200, 600, 600)

cropped_image = image.crop(box)

cropped_image.save('cropped_image.jpg')

This is the resulting image:

The Python Imaging Library uses a coordinate system that starts with (0, 0) in the upper left corner. The first two values of the box tuple specify the upper left starting position of the crop box. The third and fourth values specify the distance in pixels from this starting position towards the right and bottom direction respectively. The coordinates refer to positions between the pixels, so the region in the above example is exactly 450x400 pixels.

Pasting an Image onto Another Image

Pillow enables you to paste an image onto another one. Some example use cases where this could be useful is in the protection of publicly available images by adding watermarks on them, the branding of images by adding a company logo and in any other case where there is a need to merge two images.

Pasting is done with the paste() function. This modifies the Image object in place, unlike the other processing functions we've looked at so far that return a new Image object. Because of this, we'll first make a copy our demo image before performing the paste, so that we can continue with the other examples with an unmodified image.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

logo = Image.open('logo.png')

image_copy = image.copy()

position = ((image_copy.width - logo.width), (image_copy.height - logo.height))

image_copy.paste(logo, position)

image_copy.save('pasted_image.jpg')

In the above, we load in two images unsplash_01.jpg and logo.png, then make a copy of the former with copy(). We want to paste the logo image onto the copied image and we want it to be placed on the bottom right corner. This is calculated and saved in a tuple. The tuple can either be a 2-tuple giving the upper left corner, a 4-tuple defining the left, upper, right, and lower pixel coordinate, or None (same as (0, 0)). We then pass this tuple to paste() together with the image that will be pasted.

You can see the result below.

That's not the result we were expecting.

By default, when you perform a paste, transparent pixels are pasted as solid pixels, thus the black (white on some OSs) box surrounding the logo. Most of the times, this isn't what you want. You can't have your watermark covering the underlying image's content. We would rather have transparent pixels appear as such.

To achieve this, you need to pass in a third argument to the paste() function. This argument is the transparency mask Image object. A mask is an Image object where the alpha value is significant, but its green, red, and blue values are ignored. If a mask is given, paste() updates only the regions indicated by the mask. You can use either 1, L or RGBA images for masks. Pasting an RGBA image and also using it as the mask would paste the opaque portion of the image but not its transparent background. If you modify the paste as shown below, you should have a pasted logo with transparent pixels.

image_copy.paste(logo, position, logo)

Rotating Images

You can rotate images with Pillow using the rotate() method. This takes an integer or float argument representing the degrees to rotate an image and returns a new Image object of the rotated image. The rotation is done counterclockwise.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

image_rot_90 = image.rotate(90)

image_rot_90.save('image_rot_90.jpg')

image_rot_180 = image.rotate(180)

image_rot_180.save('image_rot_180.jpg')

In the above, we save two images to disk: one rotated at 90 degrees, the other at 180. The resulting images are shown below.

By default, the rotated image keeps the dimensions of the original image. This means that for angles other than multiples of 180, the image will be cut and/or padded to fit the original dimensions. If you look closely at the first image above, you'll notice that some of it has been cut to fit the original height and its sides have been padded with a black background (transparent pixels on some OSs) to fit the original width. The example below shows this more clearly.

image.rotate(18).save('image_rot_18.jpg')

The resulting image is shown below:

To expand the dimensions of the rotated image to fit the entire view, you pass a second argument to rotate() as shown below.

image.rotate(18, expand=True).save('image_rot_18.jpg')

Now the contents of the image will be fully visible, and the dimensions of the image will have increased to account for this.

Flipping Images

You can also flip images to get their mirror version. This is done with the transpose() function. It takes one of the following options: PIL.Image.FLIP_LEFT_RIGHT, PIL.Image.FLIP_TOP_BOTTOM, PIL.Image.ROTATE_90, PIL.Image.ROTATE_180, PIL.Image.ROTATE_270 or PIL.Image.TRANSPOSE.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

image_flip = image.transpose(Image.FLIP_LEFT_RIGHT)

image_flip.save('image_flip.jpg')

The resulting image can be seen below.

Drawing on Images

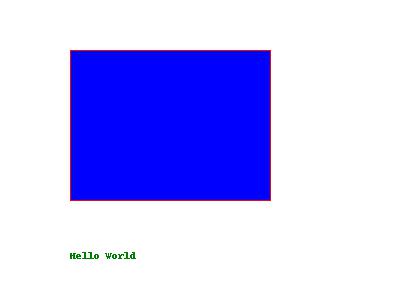

With Pillow, you can also draw on an image using the ImageDraw module. You can draw lines, points, ellipses, rectangles, arcs, bitmaps, chords, pieslices, polygons, shapes and text.

from PIL import Image, ImageDraw

blank_image = Image.new('RGBA', (400, 300), 'white')

img_draw = ImageDraw.Draw(blank_image)

img_draw.rectangle((70, 50, 270, 200), outline='red', fill='blue')

img_draw.text((70, 250), 'Hello World', fill='green')

blank_image.save('drawn_image.jpg')

In the example, we create an Image object with the new() method. This returns an Image object with no loaded image. We then add a rectangle and some text to the image before saving it.

Color Transforms

The Pillow library enables you to convert images between different pixel representations using the convert() method. It supports conversions between L (greyscale), RGB and CMYK modes.

In the example below we convert the image from RGBA to L mode which will result in a black and white image.

image = Image.open('unsplash_01.jpg')

greyscale_image = image.convert('L')

greyscale_image.save('greyscale_image.jpg')

Aside: Adding Auth0 Authentication to a Python Application

Before concluding the article, let's take a look at how you can add authentication using Auth0 to a Python application. The application we'll look at is made with Flask, but the process is similar for other Python web frameworks.

Auth0 offers a generous free tier to get started with modern authentication.

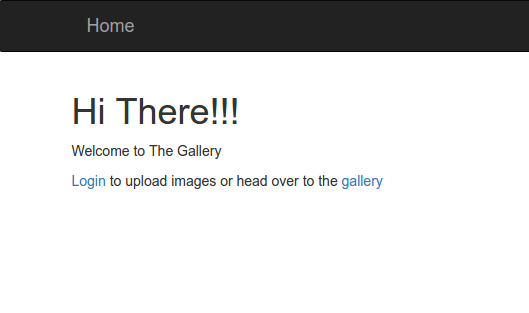

Instead of creating an application from scratch, I've put together a simple app that you can download to follow along. It is a simple gallery application, that enables the user to upload images to a server and view the uploaded images.

If you downloaded the project files, you will find two folders inside the main directory: complete_without_auth0 and complete_with_auth0. As the name implies, complete_without_auth0 is the project we'll start with and add Auth0 to.

To run the code, it's better to create a virtual environment and install the needed packages there. This prevents package clutter and version conflicts in the system’s global Python interpreter.

We'll cover creating a virtual environment with Python 3. This version supports virtual environments natively, and doesn't require downloading an external utility (virtualenv) as is the case with Python 2.7. Any version above 3.0 will do.

After downloading the code files, change your Terminal to point to the completed_without_auth0/gallery_demo folder.

$ cd path/to/complete_without_auth0/gallery_demo

Create the virtual environment with the following command.

$ python3 -m venv venv

Then activate it with (on MacOS and Linux):

$ source venv/bin/activate

On Windows:

$ venvScriptsactivate

To complete the set-up, install the packages listed in the requirements.txt file with:

$ pip3 install -r requirements.txt

This will install flask, flask-bootstrap, dotenv, pillow, requestspackages and their dependencies.

Then finally, run the app.

$ python app.py

Open http://localhost:3000/ in your browser and you should see the following page.

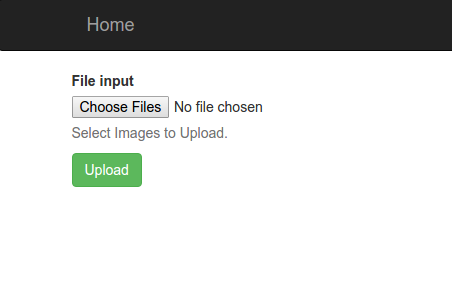

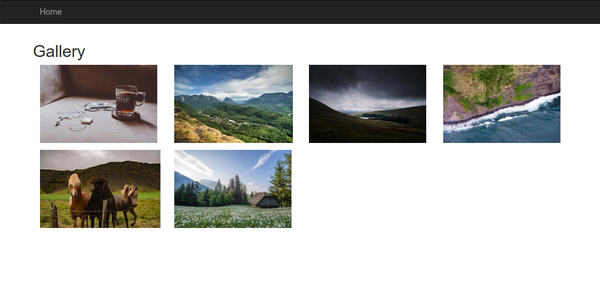

When you head over to http://localhost:3000/gallery, you'll see a blank page. You can head over to http://localhost:3000/upload and upload some images that will then appear in the Gallery.

When an image is uploaded, a smaller copy of it is made with the thumbnail()function we looked at earlier, then the two images are saved - the original to the images folder and the thumbnail to the thumbnails folder.

The gallery displays the smaller sized thumbnails and only shows the larger image (inside a modal) when a thumbnail is clicked.

As the app stands, any user can upload an image. This might not be ideal. It might be better to put some protection over this action to prevent abuse or to at least track user uploads. This is where Auth0 comes in. With Auth0, we'll be able to add authentication to the app with a minimum amount of work.

For the simplicity of the app, most of its functionality is in the app.py file. Here, you can see the set route handlers. The upload() function handles calls to /upload. This is where images are processed before getting saved. We'll secure this route with Auth0.

from flask import Flask, render_template, redirect, url_for, send_from_directory, request

from flask_bootstrap import Bootstrap

from PIL import Image

from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename

import os

app = Flask(__name__)

Bootstrap(app)

APP_ROOT = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__))

images_directory = os.path.join(APP_ROOT, 'images')

thumbnails_directory = os.path.join(APP_ROOT, 'thumbnails')

if not os.path.isdir(images_directory):

os.mkdir(images_directory)

if not os.path.isdir(thumbnails_directory):

os.mkdir(thumbnails_directory)

Setting up Auth0

To set up the app with Auth0, first sign up for an Auth0 account, then navigate to the Dashboard. Click on the New Client button and fill in the name of the client (or leave it at its default. Select Regular Web Applications from the Client type list. On the next page, select the Settings tab where the client ID, client Secret and Domain can be retrieved. Set the Allowed Callback URLs to http://localhost:3000/callback and Allowed Logout URLs to http://localhost:3000/ then save the changes with the button at the bottom of the page.

Auth0 provides the simplest and easiest to use user interface tools to help administrators manage user identities including password resets, creating and provisioning, blocking and deleting users. A generous free tier is offered so you can get started with modern authentication.

Back in your project, create a file labelled .env and save it at the root of the project. Add your Auth0 client credentials to this file. If you are using versioning, remember to not put this file under versioning. We'll use the value of SECRET_KEY as the app's secret key. You can/should change it.

AUTH0_CLIENT_ID = 'YOUR_AUTH0_CLIENT_ID'

AUTH0_CLIENT_SECRET = 'YOUR_AUTH0_CLIENT_SECRET'

AUTH0_CALLBACK_URL = 'http://localhost:3000/callback'

AUTH0_DOMAIN = 'YOUR_AUTH0_DOMAIN'

SECRET_KEY = 'F12ZMr47j3yXgR~X@H!jmM]6Lwf/,4?KT'

Add another file named constants.py to the root directory of the project and add the following constants to it.

ACCESS_TOKEN_KEY = 'access_token'

APP_JSON_KEY = 'application/json'

AUTH0_CLIENT_ID = 'AUTH0_CLIENT_ID'

AUTH0_CLIENT_SECRET = 'AUTH0_CLIENT_SECRET'

AUTH0_CALLBACK_URL = 'AUTH0_CALLBACK_URL'

AUTH0_DOMAIN = 'AUTH0_DOMAIN'

AUTHORIZATION_CODE_KEY = 'authorization_code'

CLIENT_ID_KEY = 'client_id'

CLIENT_SECRET_KEY = 'client_secret'

CODE_KEY = 'code'

CONTENT_TYPE_KEY = 'content-type'

GRANT_TYPE_KEY = 'grant_type'

PROFILE_KEY = 'profile'

REDIRECT_URI_KEY = 'redirect_uri'

Next, modify the beginning of the app.py file as shown (from the first statement to the point where Bootstrap is instantiated).

from flask import Flask, render_template, redirect, url_for, send_from_directory, request, session

from flask_bootstrap import Bootstrap

from PIL import Image

from werkzeug.utils import secure_filename

from dotenv import load_dotenv, find_dotenv

from functools import wraps

import os

import constants

import requests

# Load Env variables

ENV_FILE = find_dotenv()

if ENV_FILE:

load_dotenv(ENV_FILE)

app = Flask(__name__)

app.secret_key = os.environ.get('SECRET_KEY')

Bootstrap(app)

Here we've imported the session, python-dotenv, functools, constants and requests modules. There is no need to install any new package. These had already been installed when you ranpip install previously.

We use dotenv to load environment variables into the file from either the .envfile or from the variables set on the System.

We then set the app's secret_key. The application will make use of sessions, which allows storing information specific to a user from one request to the next. This is implemented on top of cookies and signs the cookies cryptographically. What this means is that someone could look at the contents of your cookie but not be able to make out the underlying credentials or to successfully modify it, unless they know the secret key used for signing.

Add the following functions to the app.py file. You can add them before the route handler definitions.

# Requires authentication decorator

def requires_auth(f):

Here we define a decorator that will ensure that a user is authenticated before they can access a specific route. The second function simply returns True or False depending on whether there is some user data from Auth0 stored in the session object.

modify the index() and upload() functions as shown.

In index() we pass some variables to the index.html template. We'll use these later on.

We add the @requires_auth decorator to the upload() function. This will ensure that calls to /upload can only be successful if the user is logged in. Not only will an unauthenticated user not be able to access the upload.html page, but they also won't be able to POST data to the route.

At the end of the function, we pass a user variable to the upload.htmltemplate.

Next, add the following function to the file.

The above will be called by the Auth0 server after user authentication. It is the path that we added to Allowed Callback URLs on the Auth0 Dashboard. Here, we use the data sent from Auth0 to make a few more calls to the Auth0 server to eventually get the user's profile. This will have various details regarding the user. We then save this to the session object.

Modify templates/index.html as shown below.

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<div class="container">

<div class="row">

<h1>Hi There!!!</h1>

<p>Welcome to The Gallery</p>

{% if logged_in %}

<p>You can <a href="{{ url_for('upload') }}">upload images</a> or head over to the <a href="{{ url_for('gallery') }}">gallery</a></p>

{% else %}

<p><a href="{{authorize_url}}" class="login">Login</a> to upload images or head over to the <a href="{{ url_for('gallery') }}">gallery</a></p>

{% endif %}

</div>

</div>

{% endblock %}

In the above, we check for the user's logged in status and display a different message accordingly.

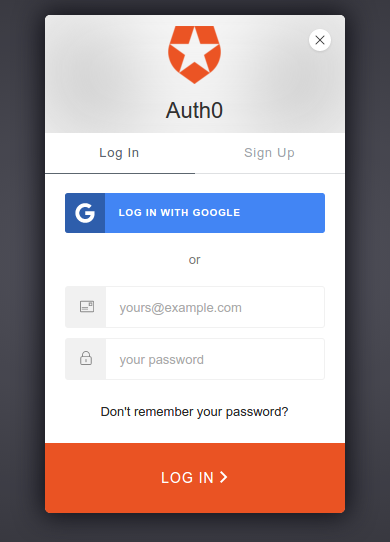

For authentication, the app will use Auth0's universal login. This will present a ready made, but customizable, login/signup form.

At the end of the code, we link to an auth.js file. Let's create this. Create a file named auth.js and save it to the public folder. Add the following to it.

Modify the index() function as shown.

In the code above we create the authorization URL and pass it in a variable to the view.

In the templates/index.html update the view to add the authorization URL in the log in link.

<p><a href="{{authorize_url}}" class="login">Log In</a> to upload images or head over to the <a href="{{ url_for('gallery') }}">gallery</a></p>

In templates/upload.html, you can add the following before the form tag.

<h2>Welcome {{user['nickname']}}.</h2>

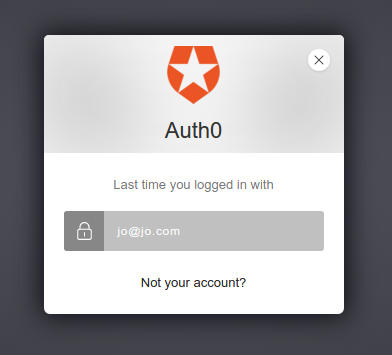

This will display the logged in user's nickname which will be the value before the @ in their email. Look at the User Profile to see what other user information is available to you. The information available will be determined by what is saved on the server. For instance, if the user only uses the email/password authentication, then you won't be able to get their name or picture, but if they used one of the available Identity Providers like Facebook or Google, then you might get this data.

Run the application. You won't be able to get the upload form by navigating to /upload. Head to the Home page and use the Login link to bring up the login widget.

After authentication, you will be redirected to the /upload.html page.

Logging Out the User

Add the following function to the app.py file.

When you are implementing the logout functionality in an application, there are typically three layers of sessions you need to consider:

- Application Session: The first is the session inside the application. Even though your application uses Auth0 to authenticate users, you will still need to keep track of the fact that the user has logged in to your application. In a normal web application this is achieved by storing information inside a cookie. You need to log out the user from your application, by clearing their session.

- Auth0 session: Next, Auth0 will also keep a session and store the user's information inside a cookie. Next time when a user is redirected to the Auth0 login screen, the user's information will be remembered. In order to logout a user from Auth0 you need to clear the SSO cookie.

- Identity Provider session: The last layer is the Identity Provider, for example Facebook or Google. When you allow users to sign in with any of these providers, and they are already signed into the provider, they will not be prompted to sign in. They may simply be required to give permissions to share their information with Auth0 and in turn your application.

In the code above, we deal with the first two. If we had only cleared the session with session.clear(), then the user would be logged out of the app, but they won't be logged out of Auth0. On using the app again, authentication would be required to upload images. If they tried to login, the login widget will show the user account that is logged in on Auth0 and the user will only have to click on the email to get Auth0 to send their credentials back to the app which will then be saved to the session object. Here, the user will not be asked to reenter their passowrd.

You can see the problem here. After a user logs out of the app, another user can log in as them on that computer. Thus, it is also necessary to log the user out of Auth0. This is done with a redirect to https://<YOUR_AUTH0_DOMAIN>/v2/logout. Redirecting the user to this URL clears all single sign-on cookies set by Auth0 for the user.

Although not a common practice, you can force the user to also log out of their identity provider by adding a federated querystring parameter to the logout URL: https://<YOUR_AUTH0_DOMAIN>/v2/logout?federated

We add a returnTo parameter to the URL whose value is a URL that Auth0 should redirect to after logging out the user. For this to work, the URL has to have been added to the Allowed Logout URLs on the Auth0 Dashboard, which we did earlier.

Finally, modify the if_else block in index.html as shown. We add a Logout link to the page if the user is logged in.

{% if logged_in %}

<p>You can <a href="{{ url_for('upload') }}">upload images</a> or head over to the <a href="{{ url_for('gallery') }}">gallery</a></p>

<p><a href="{{ url_for('logout') }}">Logout</a></p>

{% else %}

<p><a href="#" class="login">Login</a> to upload images or head over to the <a href="{{ url_for('gallery') }}">gallery</a></p>

{% endif %}

Run the app and you should now be able to log out.

Conclusion

In this article, we've covered some of the more common image processing operations found in applications. Pillow is a powerful library and we definitely haven't discussed all it can do. If you want to find out more, be sure to read the documentation.

If you're building a Python application that requires authentication, consider using Auth0 as it is bound to save you loads of time and effort. After signing up, setting up your application with Auth0 is fairly simple. If you need help, you can look through the documentation or post your question in the comment section below.